What Is Gelato?

How does one explain, in a few short paragraphs, something that’s such a critical part of Italian life, like gelato? If you’ve spent any time in Italy, it’s hard to look anywhere and not see an Italian balancing a cono di gelato in someone’s hand. Everyone, from suave businessmen in Armani suits to grandmothers chatting on a stroll with friends—all eat gelato. Like the concentrated shots of espresso taken from morning until night, it’s a part of Italian life and consumed everywhere. Even granita di espresso is served on a roll for breakfast in the south of Italy.

Gelato means ‘frozen‘ in Italian, so it embraces the various kinds of ice cream made around the country, and that’s the best definition one can offer. More than other countries, Italian cooking is fiercely regional: In the north, near Torino (Piedmonte), the food is very earthy with white truffles and hazelnuts appearing in various dishes. At the other end of the boot is Sicily, where the climate is much warmer so the flavors lean towards citrus and seafood. And in between are lots of villages and regions, including the Emilia-Romagna, Umbria, Campania, Tuscany, and Puglia, among others.

The gelato made in the north of Italy, where it’s cooler is richer, often made with egg yolks, chocolate, and most famously, with gianduja, the silky-smooth hazelnut and milk chocolate paste. In the south, ice creams are lighter, and flavored with lemons and oranges. In Sicily, granite are prevalent; slushy shaved ices that are almost served like a drink, with a spoon and a straw to slurp them up, as well as fruit-flavored sorbetti.

But getting back to gelato…as mentioned, gelato means Italian ice cream. But what makes it different? For the most part, the machines used to make gelato move very slowly as they churn, introducing little air into the mixture so the finished gelato is dense and thick. Unlike standard ice cream-making machines, usually the ‘dasher’ (paddle) moves up and down while the canister turns in a gelato-machine, so little air is whipped into the mixture while it churns. In addition, the storage freezers used for holding gelato tend to be kept a few degrees warmer (up to 10 degrees F) than a normal ice cream dipping cabinet, so the gelati keeps its silky, creamier texture. When gelato is less-cold, your mouth doesn’t get ‘frozen’ and you can taste the flavors better, according to Italians.

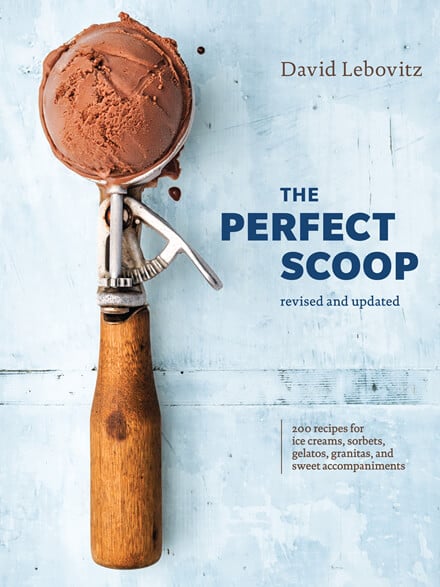

When no egg yolks or cream are in the base, the gelato will highlight the highly-concentrated taste of what’s been added, like chocolate, coffee, or whatever flavoring is used, with less fat to coat your palate or intrude. Italian food expert Faith Willinger notes that in the south, cornstarch or even wheatstarch is used to thicken the gelato base rather than egg yolks and there is a recipe for cornstarch-based ice cream in my book, The Perfect Scoop, if you want to try one yourself.

Gelato is known to have less fat than traditional ice cream. When I visited Tèo’s in Austin, owner Matt Lee, who spent a year making gelato in Florence, told me that his gelati average about 4-5½% butterfat whereas ‘premium’ brands of store-bought ice cream clock in at somewhere around 16-18%, or higher. He opened his shirt to show me his defibrillator that he wears, to prove his allegiance!

Gelato-Related Links and Resources

Tasting Rome: Gelato, Pasta, and the Market

A visit to Teo’s Gelato in Austin, Texas.

Italy’s fabulous Grom comes to Paris.

Pistachio Gelato (Recipe)

Il Gelatuaro gelato in Bologna.

Espresso Granita Affogato (Recipe)

My favorite gelato stops in Rome including Giolitti.

And another visit to Rome gelaterias.

New York’s Il laboratorio del gelato is considered one of the best gelaterias in America.

Where to find the best ice cream in Paris.

Chocolate Sherbet (Recipe)

Judy, the Divina Cucina, lists her favorite gelaterias in Florence.

Sara’s Tour di Gelato, lists favorite addresses in Italy.