Case Vecchie and the Anna Tasca Lanza Cooking School

My life seems to have, as they say in modern-speak (or whatever you want to call it), a “long tail.” Which means that what I do today, or did in the past, will continue to have meaning. Fortunately, that’s not true for everything (I can think of a few incidents in the past that are better left back there…), but something that’s stayed with me forever was getting to meet some of the great cookbook authors, cooks, and chefs from all over the place when I worked at Chez Panisse.

One such person was Anna Tasca Lanza, who not only had the noble title of marchese, but also was an acclaimed Sicilian cook. I’d met The Marchese when she came to Chez Panisse. Her philosophy of cooking — mostly farm-to-table, relying on local producers for most of what she cooked — is a natural way of life on this rugged island.

And in spite of her lofty credentials and sophistication, she was a big proponent of country cooking and the Sicilian way of life, following the seasons, using what the local land produced, in her cooking.

She planted gardens with pistachio, lemon, citron, and mulberry trees. Peppers grow abundantly, as do cardoons, eggplant, zucchini (and their bright yellow flowers), and artichokes.

Tomatoes, of course, figure heavily in Sicilian cooking. At Case Vecchie, which has been in the family for over 200 years, ripe tomatoes are put up in all sorts of ways. Opening the top of their salsa di pomodoro is like uncapping the taste of a Sicilian summer. And the remarkable tomato paste, estratto di pomodoro, is so fruity and sweet, they spread it on toast for breakfast in the summer.

In her book, The Heart of Sicily, Anna Tasca Lanza explains the lengthy process that begins with her and five assistants cooking 400 pounds of tomatoes –in two batches – in cauldrons over an open fire, each tomato being seeded by hand. After nearly an hour of constant stirring, to avoid burning, each batch is salted, covered, and left to stand overnight.

The next day, it’s strained, spread on cloth-covered tables, and left in the strong sun a few days until it’s thick and clay-like. As it’s concentrating, the tomato paste is scraped from 12 tables onto one, dried a little more before being kneaded with oiled hands and conserved. Whew! I’m exhausted just recounting it.

Anna passed away a couple of years ago, and Fabrizia Lanza, her daughter, stepped up to the plate and took over the gardens that her mother planted, as well as her cooking school.

At Case Vecchie, the farm buildings where she lives with a substantial kitchen and rooms for guests, she continues to focus on local producers and products, creating a marvelous line of honey, grape syrups, and that heavenly estratto di pomodoro (tomato paste), that was so good, I had to squeeze two jars of it into my carry-on.

(Actually, I bought so much stuff, including some gorgeous Sicilian pottery, that they’re shipping a case back to me in Paris. Which is great because I would have flipped out if it had been confiscated by security at the airport.)

One thing I couldn’t take home was the wine from Regaleali, their winery, which was a real shame, because it was only €1,04 per liter (about $1.25 per quart). But locals take advantage, and come with their own containers for a “fill up.”

Sicily is a special, and complicated place, where the Tasca family has a long history. In the kitchens are a team of women, many are members of families that have been working with the family for generations. Although it wasn’t scheduled, I couldn’t help myself from jumping in and giving the the women a hand with the pastries. In fact, I was having such a good time cooking with them that I skipped a wine tasting to make rustic little fruit crostate with them (the ones shown at the top of the post), for the 25th anniversary party of the cooking school the following day. After all, everyone knows all the fun is in the kitchen. Right?

I did make it over to the lunch that took place after the wine tasting, which started with a delicious soup made with squash greens and pasta, and ended with stacks of breaded disks, known as latte fritto, or fried custard. So it wasn’t all work and no play. Or vice-versa.

Fabrizia invited me, along with others, to take part in the festivities. And in the days leading up to the party, Fabrizia made meals for us, including a timbale of eggplant filled with pasta that was the essence of simplicity–just deep-fried eggplant slices fitted into an oiled pan dusted with breadcrumbs, then filled with pasta, before being sealed closed with more eggplant, and baked until the outside crisped up and caramelized.

Fabrizia told me they used a lot of breadcrumbs in Sicily, since their history was a cuisine of poverty and absolutely nothing was wasted. (Like the recycled whey the pecorino-makers use to make ricotta.)

For the anniversary celebration of the cooking school, Fabrizia had planned an enormous lunch to showcase the products from local producers that she and the kitchen team prepare each season, dubbed by Fabrizia as “arm-to-table” cooking.

Forget what you heard about excitable Italians. When the remarkably calm Fabrizia told me how many people were arriving, I didn’t believe her at first because there wasn’t a hint of stress in her voice or manner, nor in the kitchen. And out in the gardens, where a long, barren patch of land was slated to be one enormous dining table, it was hard to believe that anything was going to happen there.

But as the days passed, men arrived from town and started digging into the earth to build a canopy. Some shaded shelters were constructed from wood and swaths of linen, to protect people from the Sicilian sun. (Or rain, as we later experienced.) And little-by-little, in the kitchen, an entire meal started coming together.

The day of the event, the guests arrived, the list swelling from 150 to nearly 200 the day before the lunch.

The Sicilians love deep-fried foods and my dream is to spend an evening in Palermo, gorging on street food, like panelle (chickpea fritters, above – a cousin of panisses, from Provence…and one of the best things ever), and crispy, tiny frittelle, filled with rice.

But I wasn’t complaining about being out in the countryside, sipping rosé and nibbling on fried snacks with a throng of friendly Italians.

There were also bins of green almonds, almonds picked before they are ripe, that you split open with a rock–or, if you’re more civilized than we are, a knife–then extract the slightly formed almond kernel inside, which is the color of ivory with a delicate crispness and a subtle nutty flavor.

While after my experience(s) at the Italian airports didn’t lead me to believe that efficiency was at the top of anybody’s list, by the day of the luncheon, where there was once a long, barren path, there was now a massive table ready to seat a couple hundred people.

At regular intervals that spanned the length of the table, were jars and bowls of things to nibble. Fortunately–or because they’re Italian–they were wise enough not to place anything out of reach. So there was easy access by all, to everything.

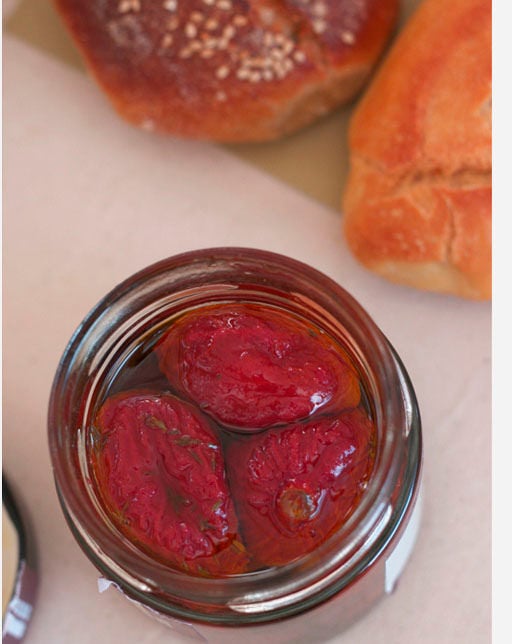

My favorite was the preserved cherry tomatoes, neatly packed in jars. After my eyes rolled back to the front of my head, I asked Fabrizia how they’re prepared and she said that each cherry tomato gets sorted by size, so they cook evenly, then each cherry tomato is hand-peeled.

After that, they’re slow-roasted in the oven for six hours, each one (yes, once again, individually), is turned by hand midway during roasting. Then they are jarred with olive oil and herbs, and preserved.

After working our way through the condiment, and Regaleali wines, bowls of food started coming out in full force, not in measly little portions, but in abbondanza!

Instead of some top-heavy meaty meal, with mounds of meat or lamb, our early summer lunch was based on Sicilian plants: bowls of chickpeas, Arborio rice with fresh mint (which is from another part of Italy, but still, I fell for it hard – I never knew rice could be so good!), lentils, and capers from Pantelleria.

The dry-farmed cherry tomatoes were so good, I’m pretty sure I can never eat any other cherry tomatoes again. And there were tiny, and beautiful little ceramic bowls of sea salt harvested in Trapani, to sprinkle about as we wished. The bowls, however, disappeared before I could add any to the box of goodies being shipped to me.

We had picked up a lot of pecorino from the cheese-maker a few days earlier, which we were welcome to drizzle with sticky-sweet Zibibbo grape syrup, made by reducing grape juice until it’s sap-like.

Even though abbondanza is usually the watchword when it comes to la cucina Italiana, dessert was an over-the-top blow-out. Men came down the outskirts of the table, hefting wooden planks with bowls of fresh cherries.

The fruit preceded the fruit crostate that I’d help make the day before, by pressing pasta frolla (short dough) into little tartlet pans (that had been buttered, and dusted with breadcrumbs, of course!), then smeared with a bit of sour cherry jam and baked with peaches that had been preserved from last year’s harvest.

A sprinkling of Bronte pistachios on top added some contrast and crunch, and the tartlets were gone in a flash.

Although I really wanted to make it through the cannoli made with sheeps’ milk ricotta, after scraping the little biancomangiare (almond custard) clean from the small metal cups they were set in, the skies did what they had been threatening to do all morning, and sent us down the hill, into the barn to escape the rain for coffee and mulberry gelato.

Perfetto.

– Many of the recipes cooked at the school and on the estate can be found in The Heart of Sicily by Anna Tasca Lanza, and Coming Home to Sicily by Fabrizia Lanza.

– You can obtain some of the products from Case Vecchie the at Naturi in Tasca