Chez Panisse at Forty

Before I started working at Chez Panisse, way back in the early 1980s, I didn’t really know all that much about the restaurant. Prior to moving to California, I’d read an article about “California Cuisine” and of all the places listed, the chef of each one had either worked at this place called Chez Panisse or cited it as inspiration. So I’d picked up a copy of The Chez Panisse Menu Cookbook, which listed menus and the recipes featured in the restaurant.

As I read through the book over and over, I was intrigued by this place where people injected tangerine juice for multiple days into legs of lamb then spit-roasting the hindquarters so that those syrupy-sweet juices not only moistened the meat but caramelized the outside to a crackly finish. There were descriptions of salads of bitter greens drizzled with walnut oil that were topped with warm disks of goat cheese, which were made by a woman who lived an hour north of the restaurant and had her own goats.

Thinking about it now, I am sure that I’d had goat cheese on backpacking trips through Europe, but never really paid attention to it. But these fresh disks of California chèvre that oozed from the bready coating that were part of one of the menus in the books sure sounded pretty good. And a tart made of sliced almonds, baked in a buttery crust until toffee-like and firm, and meant to be eaten with your hands, along with tiny cups of strong coffee alongside. I kept that book on my nightstand for bedside reading for months.

The stories of each of these meals, back then, was a revolutionary idea. Yes, there were lofty French cookbooks regaling us with menus featuring aspics and crowned rack of lamb, each tip garnished with a small, ruffled turret of starched white paper. And there were American cookbooks that talked about foods from various parts of our expansive country and culture, with recipes to prepare them. But the idea of foraging around where you lived, finding the ingredients in your community, and presenting them simply (with permission to enjoy them along with hearty red wine) was something one might come across in a recounting of a French auberge, but not in American. After reading through that book, something told me that I had to go work in that restaurant.

I took a little bit of a detour before I arrived for my first shift at Chez Panisse, working in other restaurants after I arrived in San Francisco, my first time living in a big city. When my best friend and roommate from college came to visit me, we had dinner in the café and after a rather long wait (which gave us ‘permission’ to drink plenty of red wine ), we had a great time – and a great meal – which was exactly what eating out with friends should be. Because I was currently working in a very difficult restaurant situation, which made me dread going to work each day, after that meal, I was determined to find a way to work at Chez Panisse.

A duo of chefs had taken over the café upstairs from the restaurant and coached me before my all-important interview, which I somehow scored with Alice Waters, the owner of the restaurant. They said to me, “When she asks you what cookbooks you read, tell her “Richard Olney and Elizabeth David.” I was still working at the other restaurant at the time and never heard of either of those two people. I was busy coping with work and I think I may have stopped in a bookstore, glanced at a copy of Richard Olney’s Simple French Cooking, and then left, but I arrived at my interview not only not having read any of the books by either of those authors, but I barely had any idea who they were.

For the interview, we sat in the front of the restaurant, at the table closest to the front window, which is the farthest place from where the cooks were going about their tasks in the kitchen, preparing the evening dinner. One sturdy woman was holding the hindquarters of a large backside of a lamb and was separating the meat from the bones clutching a giant cleaver in her fist. I never saw anyone do that before and she looked up at me when I walked by her and said “Hi there”, then went back to butchering the lamb.

I later learned that Alice had to conduct interviews away from the point farthest from the kitchen because if she was anywhere near where the food was being prepared, it was impossible not to jump up and run into the kitchen to taste something, or ask (or advise) someone how they were going to prepare something. And she was not shy or hesitant to correct them if she felt something was wrong.

I don’t remember all that much about the interview but I was slightly terrified as this little woman shot questions at me about what I ate at home. “Popcorn and tortilla chips”, I told her, pleading my case that as a line cook I didn’t have time to shop, or eat at home. When that all-important moment came and she finally asked me what cookbooks I read, I was never good at lying, and blurted out, “The Joy of Cooking.”

To this day, I’m not sure what got me the job. (Although I am sure it wasn’t my trial shift, that started off with someone asking me to peel an enormous pile of pinky-size baby carrots, and when I finished an hour or so later and saw them dumped into a large pot to be pureed into soup – and said, incredulously “That’s what I peeled all those tiny carrots for?!”) But somehow, I was meant to be part of Chez Panisse and got the job.

I ended up working at the restaurant for thirteen years. When I started at the restaurant, few people in America – myself included – knew what arugula, blood oranges, green garlic, goat cheese, radicchio, heirloom tomatoes, or baby lettuce were. (Later I found out that Alice hired me because I said that my favorite food was salad, and washing the lettuce was her favorite part of working in the restaurant.) Many of these things were imported back then because they just weren’t available locally. But during my years at Chez Panisse, white peaches, fraises des bois, clementines, frisée, and French butter pears started appearing at the backdoor of the kitchen from locals that “…just happened to have a tree and heard that we were using them.” And just like us (and me), our guests were learning about all these things, like lamb didn’t necessarily come in shrink-wrapped packages. They were astonished for find out that radicchio wasn’t “red cabbage.” Nor did red wine have to come from France or Italy, but what could be found a few miles away rivaled what was available elsewhere.

After my first year at the restaurant, I migrated to the pastry department, which was located just next to the backdoor and we were the first to see everything that came in to the kitchen. Alice instructed everyone to just buy anything beautiful – and delicious: money was no consideration and we bought whatever was special that day then served it as soon as possible. It’s a pretty crazy way to run a restaurant, one that’s pretty unimaginable anywhere else. But we went with the flow, and somehow it all worked.

This month Chez Panisse turns forty and thinking about it, I worked there for one-third of the life of the restaurant. Two co-workers of mine had come to Paris a few months ago, separately, and since we were all in town at the same time, we decided to have dinner together. Back then, I was on the fence about going to the anniversary celebration. I’d planned to go when I got a message about it last winter, but then a trip to New York came up and I thought that two trips to the states in one month was too much for me. I’ve been particularly swamped with a few projects and all sorts of French paperwork that have been keeping me over-occupied, plus the idea of getting on a plane and heading halfway around the world wasn’t all that appealing. (Sticklers will likely point out that it’s not exactly halfway, but fourteen hours of flying certainly feels like it to me.)

When I saw my co-workers and friends, who I hadn’t seen in over ten years, we ordered a big plate of charcuterie, some cheese, and started with a chilled bottle of white wine from the Loire, it was like a single shift at the restaurant hadn’t passed between us. Sure, I had moved half-way around the world (nearly), one had retired from waiting tables, and the other ran a wine importing business, but the thing that I loved at Chez Panisse the most were not only the long-standing friendships and family that were created, but how they’ve endured and no matter what we do in our lives, or where we go, we’re all connected by being a part of the restaurant.

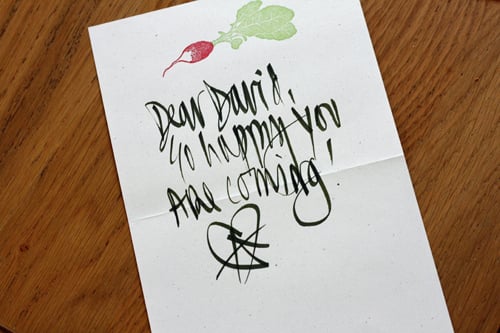

A few bottles of wine later, I was fairly sure that I didn’t have much of a choice but to head back for the anniversary events. And I was still on the fence a few days later when the real clincher arrived, along with my invitation, from the top:

As part of the pastry station, we had a marble that we used for rolling out pastry, which also made an impromptu place where friends could pull up a stool and dine with us. (Well, the ones that didn’t mind getting splashed with fish juice or leaving to find their backside dusted with flour.) Shortly before I left Chez Panisse, Alice was having dinner at the marble, but keeping an eye on the plates that the savory cooks were getting ready to go out into the dining room, while I was preparing desserts for the night. I don’t remember how the subject came up but I said to Alice, “You know, I’ve been working here for thirteen years, and I’m still afraid of you.” And she put down her wine glass, looked at me with her little brown eyes, smiled at me ever-so-slightly, and said — “Good.”

A lot has happened since I left in 1998, but many times when I heft a nectarine at the market and give it a good sniff for ripeness, or toss a bowl of bitter radicchio leaves with bits of chèvre and some blood orange slices and take a critical taste, wondering if it’s balanced correctly, or if my chocolate sauce going on my profiteroles needs to be more bitter, less sweet, I remember everything I learned working at Chez Panisse, especially getting it right. Indeed, the restaurant was – and still is – a vital part of who I am, no matter how often I see my friends and former co-workers, or where I live.

On the plane to San Francisco yesterday, the meal was mostly forgettable. (In their defense, it’s hard to be “local” when you’re 12,000 meters in the air.) I picked through my boneless skinless chicken breast and plastic-wrapped roll—just to be polite. But when I started in on the salad, rifling through the few leaves of lettuce in the plastic cup, which were just starting to brown at the edges, tucked in between those wilting leaves were little bits of radicchio, I looked around and everyone on the plane was eating them, as if nothing at all was unusual.