The Coopers of Cognac

Earlier this week, I woke up in a small town, smelling of something. It wasn’t anything bad. In fact, it was pretty good: sweet, caramel-like, and roasted, with a vague, but lingering aftermath of alcohol following it. It wasn’t something I was used to, but I’d tasted so many Cognacs this week in the town of Cognac, that it was literally wafting out my pores. And I’m not complaining.

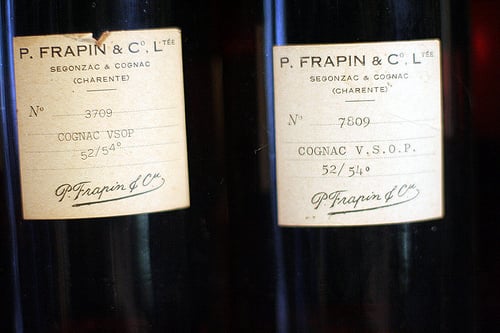

Three days in the region is barely enough time to scratch the surface of this well-known brandy, which honestly, I didn’t know all that much about when I was invited to the annual Cognac auction, where bottles worth thousand of euros are bid on by a few lucky (and loaded) individuals.

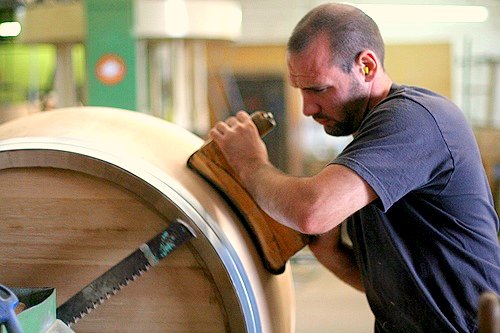

But the first thing I learned about Cognac, is that it all starts in the barrels at the tonnellerie, or cooperage, where the barrels are made. As I touched on in my post about fresh shelling beans, and several people left their own thoughts in the comments, we’re often unaware of what actually goes in to producing the food—and beverages, that we feed ourselves.

For example, I had no idea that it takes three years, minimum, just to make each barrel that’s used for aging.

From the selection of oak, mostly from France (with some coming from the US), the wood that these men get needs to be cured for a minimum of two years with an alternating system of watering, then drying, during which time it changes color and becomes less-porous, and starts its journey to becoming a barrel.

One thing that struck me is that even though we’re living in a pretty modern age (that is, except for my telephone and internet provider*), barrel-making hasn’t likely changed all that much in the last few centuries. Sure there’s machines to cut the wood, but the finishing and banding is all done by hand. And I was surprised to see that they even make the saws that they use to cut the wood by hand as well. If there’s any outsourcing, I didn’t seen any evidence of it.

Aside from ensuring that the men in the region don’t need to go to the gym, the long curing of the barrels reduces their humidity so when the distilled liqueur is stored in there, only 3- to 4% evaporates every year, which is called the Part des anges, or the angel’s share.

So not only does the Cognac age in these barrels, but the flavors become more concentrated and take on that deep, aged color courtesy of the coopers.

The youngest Cognac, VS (Very Special) is aged around 2 years, VSOP Cognac (Very Superior Old Pale) is aged for at least 4 years, and the most time one would spend in one of these barrels is 70 years.

I didn’t know what all those terms meant before I came here, but like anything, the taste of what’s in the glass is much more important than the terminology. And I tasted quite a few new and old Cognacs, and although I have a preference for the more mature specimens, younger isn’t necessarily worse. I mean, for brandy.

By day #3, if someone lit a match near me, I likely would’ve imploded (But what a way to go!) I didn’t want to leave the fellows and their tools, but I had other things to do…

Next Up: What I drank, and more…

*Apologies if I’ve been out of touch. I had a FIM (France-induced meltdown) because both my telephone and internet still aren’t working, after seven weeks. (My provider refuses to send someone over, or to help in any way, so I’m in the process of trying to wend through a staggering maze of bureaucracy to change providers.)

It’s vaguely amusing when you’re trying to buy a light bulb or masking tape and no one will help you, but it’s another thing when you’re cut off from all forms of communication and they make the situation impossible to resolve, even in person. So excuse any typos, grammatical errors, or bêtises, while I work and post from various places.

Now excuse me, I think I need another glass of Cognac…