Food: Transforming the American Table 1950-2000, at the Smithsonian Museum

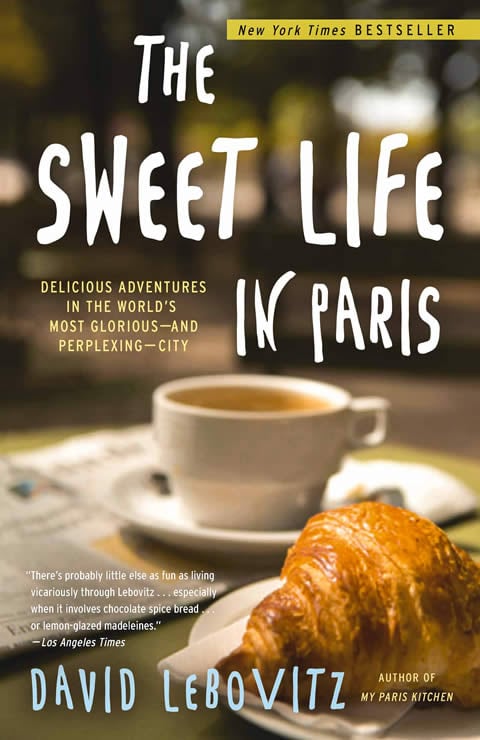

Unfortunately, book tours offer little – if any – free time. Sometimes you want to check out places that are miles away from your hotel, which are hopeless causes (although not always). But since publishers and venues are flying you around, they’re not footing the bill for a leisurely evening with friends, or with copious time to explore the city. (And I don’t blame them.) So you value every precious second you have. Your best bet is to remain within a close radius of your hotel. If you’re fortunate, you can race to a Japanese restaurant, cafe, or doughnut shop. Other times, you’re happy to lie in a nice bed and watch “The View.”

For the most part, the weather on my tour was spectacular. And while I can’t take credit for that, still, people thanked me for bringing sunny skies with me, wherever I went. In Seattle, I hit the city during one of the rare thirty days of sunshine (out of 365 days.) But not always. Heading to Miami, just as we were poised to take off on the runway, our plane turned around and headed back to the gate to get more fuel because a hurricane warning in Florida, which might force us to land elsewhere. (We ended up arriving okay, but we circled high above the Miami airport for a couple of hours, waiting for it to reopen.) Yet the next day in Miami, the skies were spectacular.

And for my last city and stop of the tour, I had the pleasure of sitting on a green, grassy lawn at the Washington, D.C. farmers’ market, in the nation’s capital, signing books and chatting to shoppers, who were loading up their baskets with bunches of asparagus, strawberries, and radishes as well as first-of-the-season tomatoes and excellent cheeses.

Since I miraculously ended up with a rare, free afternoon the following day, I hoofed it over to the National Museum of American History at the Smithsonian, to check out Food: Transforming the American Table, 1950-2000.

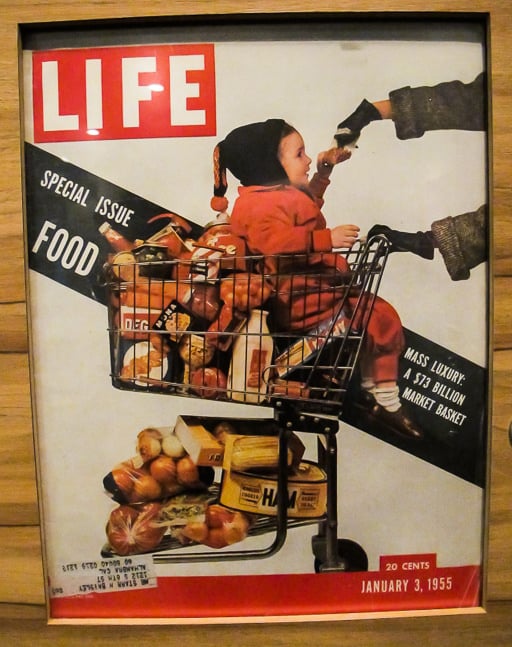

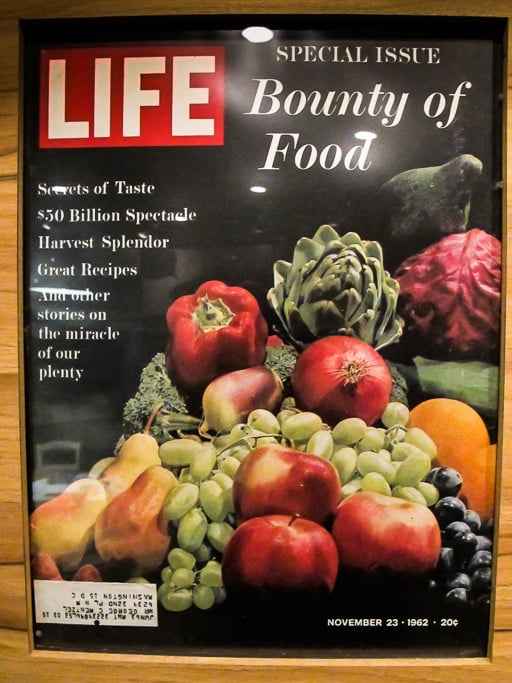

The exhibit highlights how American eating and shopping habits have changed during those five decades, and the museum compiled this retrospective to show the progression and evolution of the changes leading up to what shows up at the American table.

Beginning in the 1950s, snacking and pre-prepared convenience foods started to become popular, often in the name of “progress,” resulting in an abundance of food that was either cheap, or quick to prepare. Or both.

Agribusiness became a much more important player in the way fruits and vegetables were grown and distributed, as we moved toward cellophane-wrapped produce, mechanical harvesters, relying less on independent farmers as the newer way of growing food was faster and cheaper. As a reaction to this, in the 70s and 80s, some began to rebel against this trend, which was responsible for a host of concerns in America, including health and ecological problems.

And as much as people like to deride places like Whole Foods and Starbucks, back in those days, it was a dream to supermarkets filled with fresh produce, organic meats, and dairy products. (I was living in upstate New York in the 1980s, buying produce from local farmers. But that was the exception.) And like ’em or not, before Starbucks existed, 99% of the coffee served in the states was diner-style coffee, sitting on a Bunn warmer for hours, simmering away to a black slurry in the bottom of the rounded glass pot. They got people used to thinking of coffee as something more than a black sludge to be tolerated.

The food revolution of the 80’s really was a revolution, radically changing how we ate, and how we perceived food.

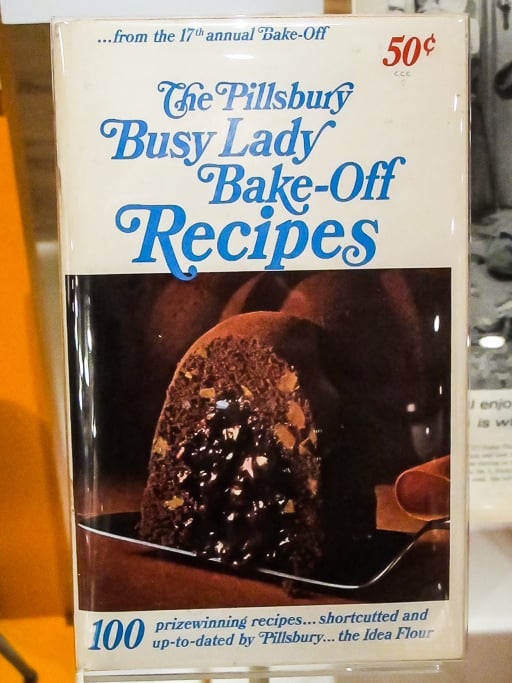

One of the main influencers came earlier. Julia Child was the antithesis of the trend during the 50s and 60s towards frozen and convenience foods, as she promoted French cuisine to Americans, which was ingredient-based, and she rarely opened a jar or can. But she wasn’t just presenting dishes and recipes; she demonstrated that good cooking, with real ingredients, was within the reach of all. Even a lanky California gal. Child turned America upside-down with her wacky antics on television, and was credited for giving public television in America a major boost. (But the museum reminds us that as popular as Julia Child was, at the same time, Peg Braken’s I Hate to Cook Book, was also wildly popular.)

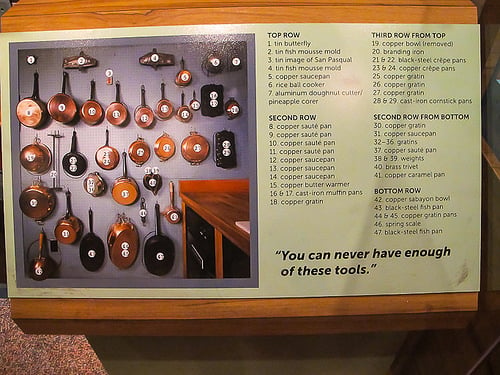

In addition to collecting copper pots and pans (above), Julia Child also embraced the food processor, a machine invented in France, calling it one of the best culinary inventions ever. The microwave oven, well – she wasn’t as impressed with that. Here’s an early example from back in 1955, manufactured by Tappan. As the museum noted, “due to its steep price of $1,295, as well as customer confusion about how to use it,” it didn’t sell well.

Later a more streamlined model, from 1976, was made in Japan and sold at JCPenney stores. It had a more customer-friendly sticker price of $219. (Although it was missing the recipe card file.)

After Julia Child passed away, her kitchen from Cambridge was reassembled in the Smithsonian, including her old, original Cuisinart food processor, a trash can conveniently located in the middle for the kitchen, her tools lined up on the walls, and, tucked in the shadows, the enormous mortar and pestle she lugged back from France. If the kitchen hadn’t been encased in protective lucite, I would have been tempted to bring it back to France. (And if my single suitcase wasn’t already stuffed. Although if they were selling them in the museum gift shop, I probably could have found room.)

In her aftermath, an era of television chefs was born, and cooking shows proliferated. At the exhibition, you could watch not only old episodes of The French Chef with Julia Child, but other cooks and chefs in their youth, like Emeril Lagasse, whose New Orleans-based cooking reflects the melting pot of the American table.

Other culinary machines allowed us to “cook, while the cook was away,” as the museum noted, with such tools as the crock-pot, patented in 1975. Additional innovations on display were Teflon non-stick pans, electric can openers (in avocado green), Corning Ware (oven-to-table cookware), Oxo tools, and one of the machines used to make “baby” carrots, developed in the late 1980s, to transform imperfect carrots into smooth, slender little orange bites, ready-to-eat.

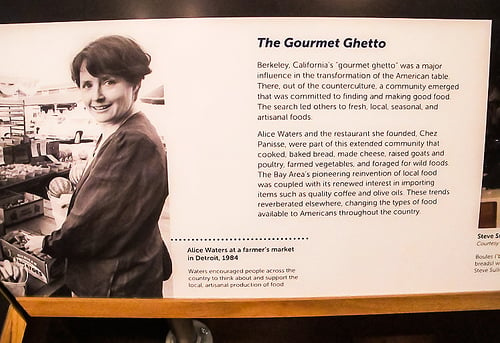

On the opposite coast from Julia, in Berkeley, the term Gourmet Ghetto, referred to the area around Chez Panisse restaurant, which was founded in 1971. (And recently celebrated its fortieth birthday.) A copper cauldron was on display at the museum, which I remember eating bouillabaisse and garbure (Gascon duck stew) from, when I was working at the restaurant.

Many culinary icons sprung from the area, such as Steve Sullivan, who was a dishwasher at Chez Panisse, who decided to spend his time late after the restaurant closed, making breads in the pastry ovens. His breadmaking eventually became Acme bakery in 1983, turning out French-style pains au levain which could rival – and in many cases, beat – the best breads in France.

Also in the area was Peet’s coffee, founded by a Dutchman, which predated Starbucks, and was known for cups of rich, dark, European-style coffee. The Smithsonian catalog notes that in the 1960s, Mr. Peet was “shocked at the poor quality of American coffee,” and decided to start small-batch roasting his own beans. Locals in Berkeley, that frequented the place, were called “Peetniks,” and three of them went on to establish Starbucks.

And of course, there is Alice Waters of Chez Panisse, whose insistence that we take more time to shop, cook, and eat, changed the American table as well, by turning the focus to fresh, locally sourced, and organic ingredients. Consequently, there are over 3000 farmers’ markets all across the United States, from small towns in the midwest, and cities like Washington, D.C. and Los Angeles, and even a sprawling Greenmarket in the middle of ultra-urban New York City.

American cuisine also embraced the multiculturalism of the country, with things like soy sauce, salsa, curry, and other ingredients and flavors that were once considered exotic, and are now common ingredients in our pantries. Wine, which was common in Europe, showed up on our tables as well, and a big part of the Smithsonian exhibition was devoted to showing how far America has come in producing and enjoying wine. (A recent story on NPR, in fact, noted how U.S. Passes France As World’s Top Wine Consumer in terms of volume, recognizing, of course, that the population in the U.S. is quite a bit larger.)

A separate showcase highlighted how Mexican cuisine has become mainstream, and foodstuffs like tortilla chips, salsa, and chiles, are readily available in America. And many of the dishes common to Mexican cooking have been integrated into our culture, perhaps more than any other cuisine.

(And perhaps to complete the circle, the Tunnel of Fudge Cake, shown on the cover of The Pillsbury Busy Lady Bake-Off Recipes booklet at the beginning of this post, bears a more than slight resemblance to the warm chocolate cakes with melting center that we enjoy today, both in America, and in France.)

Seeing the exhibition was a great way to spend my last day in the United States, reflecting on where we’ve been, and how far we’ve come, in the last few decades. If you can’t make time to see the exhibition in person, as I was fortunate to find the time to do, there is an excellent online exhibition with photographs, artifacts, and additional information, you can check out.

On a related note, I’d like to thank everyone who came to one of my book events and signings to say hi. It was my first full-on book tour and I covered a lot of ground in a month. (Friends who had done book tours told me I was nuts.) But in spite of the hectic schedule, and lots of traveling (and having to pick up an extra suitcase), it was great to meet so many of you in person. And while I wasn’t able to respond to all the messages, posts, tweets, photos, and messages, I’m glad that others had as good of a time as I did on my tour.

I’d especially like to thank the people who cooked meals at the restaurants and venues, and worked at the presentations I gave. You were all a pleasure to work with, and big part of the success of my trip. The food everywhere was amazing and it was nice to hang out with such dedicated chefs, cooks, and people who worked not only in the kitchens, but at the farmers’ markets, shops, conferences, schools, and bookstores. A bientôt! – David