A Visit to Abu Kassem Za’atar Farm

One thing you learn quickly if you travel to, or somehow explore otherwise, the various cuisines of the Middle East, is that every country, and seemingly…every single person, has their own idea of what za’atar is. And they’re very (very) attached to it. So much so that a chef in a restaurant in Jerusalem rolled up his sleeve to show me a tattoo of what he told me was hyssop, a name for an herb that’s used in some places to make Za’atar, one of the world’s great seasonings.

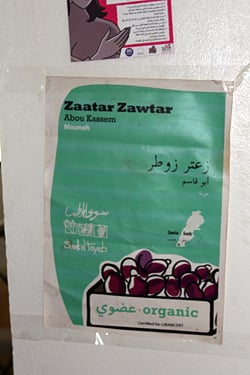

Za’atar consists of herbs, sesame, and sumac, varying them by proportions depending on culture and country. But I can say that Abu Kassem of Za’atar Zawtar makes the best za’atar I’ve ever tasted, anywhere.

Standing in the middle of his field, watching him pull the herbs out of the ground, then going back to his small gas burner and mixer, and watching him make up a batch that you’re going to sprinkle all over your lunch in a few hours – well, it’s hard to believe that za’atar could get any better.

When I went to Lebanon one of the first places my friend Bethany of Taste Lebanon took me to visit was his farm and one-room production facility. She’s spent the previous day telling us how great his za’atar was, and how lovely he and his wife were. And she wasn’t kidding.

I was surprised as you might be to learn that za’atar isn’t just a seasoning blend; it’s actually the name for an herb, which starts off its life looking a bit like standard oregano. But the plant is called za’atar in Lebanon, the same name as the seasoning. (There is an interesting explanation over at What is za’atar at Desert Candy which goes into detail of the similarities and confusion between the two.)

But everyone in Lebanon, and in other countries in the Middle East, have varying ideas about what goes into za’atar. And as I traveled through Lebanon and visited various bakeries, folks would come in and hand over a container of their own za’atar to the bakers (and often some of their own olive oil as well), where they would roll out and bake up oily flatbreads known as man’oushet za’atar, which people would come back later and pick up. And which I, myself, could not tear into enough of while I was there.

After a few minutes of looking at the plants growing around his house, we found ourselves standing in front of a long table with a suspiciously high stack of plates and glasses. Which, having already spent a few days in Lebanon, I knew what that meant – another great meal was ahead. The Lebanese are known for their hospitality, so not wanting to be rude, I quickly took a place at the table, right as the cavalcade of dishes from the kitchen of Abu’s wife Fatima, came tumbling out.

In addition to the warm man’oushet (also called manouche), were cracker-like breads, which Bethany was surprised to see as she told me they were a specialty bread, and not easily available.

All the breads were lovely, as was the labneh and hard-cooked eggs from their chickens. But I had my own – recipe, please! – moment when Fatima ladled me a bowl of the best foul I’ve ever tasted. When I asked how she made it, in between spooning it up as fast as my little spoon-holding hand could carry me, she smiled, blushed, and modestly waved me away. Honestly, I didn’t know beans could taste so good.

Like most meals in Lebanon, you eat and eat and eat and eat. And then eat and eat some more. But you don’t feel overstuffed because the food is healthy and fresh. And it’s so good, that you don’t want to stop.

And when za’atar, which has been grown, picked, and mixed just a few feet away from where you’re eating, is scattered over everything, it’s hard not to gobble everything down that’s put in front of you.

Less-tasty was the za’atar oil that Abu was distilling. I’d not heard of za’atar oil, but I’d had za’atar beer from 961 Beer, so thought I should give it a shot.

My friend Anjali and I tasted the water from the distillation, and it was so incredibly strong and completely undrinkable, so utterly what I never-want-to-put in my mouth again – imagine a truckload of herbs being reduced to a single drop – that you’d understand what I mean if you even tasted a drop of it.

Abu made a bunch of health claims that he associated with za’atar oil and za’atar water, which I won’t repeat here, except to say that anyone who can get through a glass of this once-a-day deserves to be free of whatever ails them. My mouth was literally numb for hours afterward. But that didn’t stop me from wanting to see how he cultivated and made his own special blend of za’atar. Abu uses equal parts za’atar, sumac, and sesame seeds in his za’atar, along with a little salt.

He said that by far the most expensive ingredient in his za’atar is the sesame seeds and said to beware of bags of inexpensive za’atar when you shop, because some less-scrupulous companies put sawdust or dirt in theirs. To combat any degeneration of Lebanese za’atar, he’s trying establish some sort of national standards to keep the quality high in Lebanon.

The fresh plant leaves are also good pickled, which I learned while trying a molded cheese called Shanklish, whose flavor is heightened by a few pickled (or fresh) leaves scattered over the salad.

And I even saw an older man at another meal snacking on za’atar leaves, mindlessly pulling them off a branch and nibbling on them, after dinner one night.

A trip to the fields gave me a first-hand look at the za’atar plants; rows and rows of deep-green leaves spread out over the Lebanese countryside.

We interrupted a turtle, making his way across the field as Abu pulled plants from the ground and telling us that in the old days, in Lebanon, an insult was saying a man was “like za’atar” because they don’t “grow” very well. (I’ll let you translate that as you wish.)

But in recent years, it’s become a compliment because the za’atar plant is known for its endurance (yup, it’s a grower!), and that it’s hard to kill.

The scent just walking around his fields was nothing short of exhilarating – breathing, absorbing, and tasting the scents and flavors of za’atar was an experience like none I’d ever had.

It’s been a few months since I visited. But I was so overwhelmed by that day with Abu that I had a difficult time trying to figure out how to sort through the experience. But I’m glad I did. (Well, except for the memories of the za’atar oil, which I don’t think I can ever forget.) And every time I reach into my bag of his za’atar that I brought home with me, the fragrance and flavor brings me back to his fields, as well being fortunate enough to have a place at their welcoming table that day.

It was a wonderful visit to one of those very special corners of the world.

– Abu Kassem’s za’atar is available in Beirut at Souk el Tayeb.

– Thanks (I think!) to Anjali for taking snaps of me.

– Other posts about my trip to Lebanon; Al Bohsali Middle Eastern Pastries, The 12-Year Old Lahham, Lebanese Meze, Saj, Flatbreads, and Lebanese Pastries, How to Eat a Falafel in Lebanon, Lebanese Breakfast, and Another Lebanese Breakfast…and Two Lunches.