About Salt

I don’t quite exactly when things shifted, but for many years, if you wanted salt you either bought granulated table salt, usually sold in a round canister for less than a dollar, or kosher salt, which came in a big box. Kosher salt didn’t get its name because it’s kosher, it’s because the bulkier crystals are a better size for salting meat, which koshers it.

If you live somewhere where your choices of salt are limited, kosher salt is usually available in any American supermarket, I recommend ditching your table salt and switching to that. But with salts now being imported and exported all over the world, the salt aisle’s gotten a lot larger, with a lot more options and choices.

Food is salted for flavor and succulence. Without it, food can taste flat. If you’ve ever tasted distilled water, which doesn’t have sodium, you’ll know what I’m talking about. Baked goods also benefit from a little salt. If a recipe doesn’t have salt in it, sometimes it’ll have baking soda (sodium bicarbonate) as an ingredient, which contains salt, as does baking powder, which contains a smaller amount of sodium bicarbonate. But even a pinch can completely make a difference, and bakers sometimes sprinkle a few flakes of sea salt over a chocolate or caramel dessert, to heighten flavors.

You don’t need to use a lot of salt, and salt is a matter of personal taste. If you’re avoiding salt, the best way to do that is to avoid pre-prepared and fast foods. A fast-food burger can have up to 1000mg of salt and a can of soup can contain 1400 to 1800mg of salt. (The FDA recommends keeping your daily salt intake under 2300mg, which is approximately 1 teaspoon. If you have any health issues, consult a doctor or medical professional for guidance on how much salt you should consume.)

In terms of succulence, salting meat in advance improves its flavor. People used to think it would dry out meat (like the butcher who served me an unsalted steak recently in France, which was flavorless), but it was the late Judy Rodgers of Zuni Café who promoted salting meat in advance, which she learned when she was cooking in France and it’s something I always do.

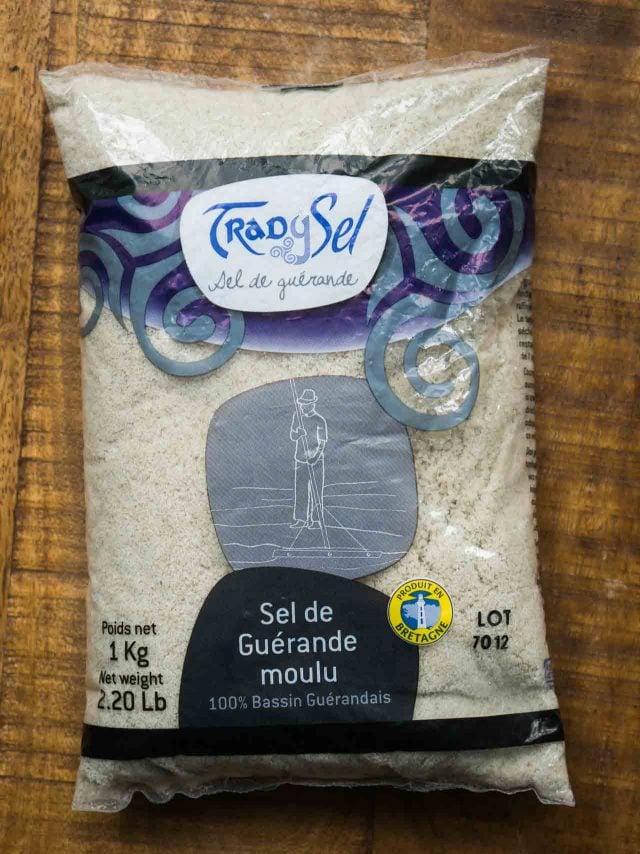

My everyday salt is sel gris, French grey salt, similar to the one above. It’s inexpensive; most supermarkets in France sell a 1kg bag of it for around €1,50 ($1.70). It’s a great deal, but even if it was three times the price, which I see it sold for outside of France, it takes me about a year to go through the bag. So I’m spending a few pennies a day to treat myself to good salt.

The main reason I use it, though, is that I like the flavor. It’s mildly salty, with a slight mineral taste. The crystals are big enough for salting meat and poultry, but small enough to dissolve in a vinaigrette or a batch of custard. If you decide to use grey sea salt, if the crystals are too large, you can grind them to a finer consistency in a mortar and pestle, blender, or food processor.

The main thing for any cook is to be familiar with the salt(s) that you use. You’ll get used to the taste and know how salty it is and after a while, it’ll become instinctive to you how much to add. So when recipes say “Season to taste,” you can gauge the right amount to your taste. In my books and recipes, I usually give a specific amount, partially because food (like soup and mashed potatoes) taste better if the salt has been cooked in it, rather than added at the table. But I advise to taste the nearly finished dish and salt it again, if desired.

Salt comes in many shapes and forms, but most cooks should have one or two types of salt on hand: A standard salt for cooking and baking, and a delicate, flaky sea salt, for finishing a dish.

Salt for Cooking and Baking

I avoid fine or granulated salt, such as the one, above on the left. Whether the fine salt comes in a round canister for 79¢ at the supermarket, or it’s a fancy one labeled “French sea salt,” or a pink one (shown at the top of the post), I find them all harsh and overly salty. If you want to taste the difference between fine table salt and flaky sea salt, put a few grains of sea salt on your tongue, taste it, then do the same with fine granulated table salt just afterward. You likely won’t be buying table salt after that.

When adding to stock or brine, the type of salt is less-important. If you’re salting stock or a pot of water for pasta, no need to use the fancy stuff, but I recommend your everyday cooking salt be something like my French grey sea salt or kosher salt. Both, I find, are similar in saltiness and the crystals dissolve when mixed in batters, doughs, and liquids. Some bakers may prefer to use fine table salt, to ensure it dissolves, but the crystals I use do dissolve in batters. (And truthfully, you won’t be able to taste much difference in a slice of cake whether you’ve used 1/4 teaspoon and 1/4 teaspoon of grey sea salt in the batter. I’m just personally more comfortable always using the same salt for everything.

I advise any cook to find a salt you like and make that your “house” salt. No one measures how much butter they swipe on their morning toast (and if they do, I’m not sure I’d want to wake up with them every morning!) so get used to your “house salt” and you’ll be a much better, and happier, cook.

Finishing Salts

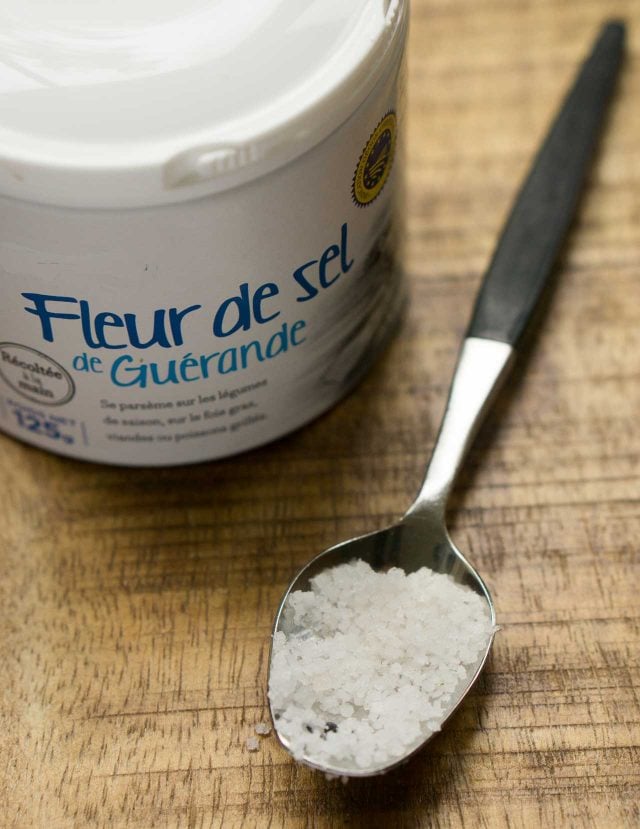

Finishing salts are salts that are added after cooking or baking, sprinkled over food right before it’s served. Because people will be crunching down on the grains or flakes of salt, a finishing salt is always a delicate sea salt.

My preferred finishing salt is fleur de sel, the top layer of mild salt that’s raked off the surface of salt marshes. To my taste, fleur de sel is just slightly salty, yet mild, and has a gentle flavor that doesn’t overwhelm, and is a flavor unto itself. French fleur de sel is harvested in the Guérande, as well as in the Camargue and the Île-de-Re. They’re all fine but I prefer fleur de sel de Guérande.

Other countries produce their own versions of fleur de sel, including Trapani salt from Sicily, Spanish flor de sal, Maldon salt from the United Kingdom, Halen Môn from Wales, and Jacobsen, which is harvested in the United States. Those are all very good finishing salts. They cost more than other salts but you really only use them by the pinch, and you’ll find a difference in how your food tastes.

Bottom Line

Have two salts in your kitchen; one for cooking and baking, and the other for finishing. Whatever salt you like/choose, get to know it and use it all the time. In a short time, you’ll instinctively learn how much to use.

Related Posts and Links

The Science of Salt (Fine Cooking)

More Tips for Perfect Steaks (Serious Eats)

The Juicy Secret to Seasoning Meat (Food & Wine)

How Pink Salt Took Over Millennial Kitchens (The Atlantic)

Salt by Mark Bitterman (Amazon)

All Salts Are Not Created Equally (Smitten Kitchen)

Salt Fat Acid Heat by Samin Nosrat (Amazon)

That’s so salt! It’s not salty enough (Chowhound)