The Black Truffle Extravaganza

When I was in Cahors, I had dinner with a French woman who teaches English. She told me one of the biggest differences between English and French is that in English, we often use a lot of words to mean one thing. And not all of them make sense. I’ve never really thought about it all that much, but she was right; we do tend to use a lot of expressions and words where one, or a few, might suffice.

“Hang a left”, “Hide the sausage”, and “Beat the rap” are a few phrases that come to mind because another day during my trip, someone was giving driving directions to a French driver, and he didn’t understand why one would “hang” a turn. (The other two phrases didn’t come up during the week, which was both good and unfortunate. And not necessarily in that order.)

But we Anglophones do have to use quite a few words to mean one thing. “That wooden tool that you use to spread crêpe batter on a griddle” is called, simply, a “râteau“.

There’s a few other culinary terms and tools that we have lengthy explanations for, when in French, one or two words would suffice. Mie is “the inside of the bread”, and “Breton cake with an insane amount of butter folded in, then caramelized” is kouign amann.

Aside from a plethora of food-related words that mean almost the same thing, such as “tentacled creatures that must be avoided at all costs”, which include poulpe, sèche, chiparons, calmars (so one must be on red alert at all times to avoid them), there are differences between an atelier, boutique, fabrique, usine, and laboratoire; all describe places where food is made and/or sold. And the people that buy raw product and do something to it can either be conditionneurs or transformeurs.

A conditionneur is someone who takes something, changes it just a little, and prepares it for sale. A transformeur takes something, changes it a little more, and prepares it for sale.

Interestingly, the woman that I had the conversation with, her mother is Anne-Marie Gaillard, a transformeur (or transformeuse?) of black truffles at her company, Henras. And I happened to meet her during the height of truffle season during my visit to Cahors.

I don’t think anything can prepare you for the smell that races quickly through your nose and makes a beeline for your brain when you walk into a room of hundreds of fresh black truffles. In fact, including the six bins in the refrigerator, soaking in what is likely the world’s most expensive water, which removes the dirt, and the four large tables where the truffles were generously tumbling about, I’d say there was maybe a few thousand in there.

Every year, during the two months of black truffle season, Madame Gaillard and her small team virtually lock themselves in this room, washing, picking, and sorting through the fresh truffles, most of which will be shipped to various restaurants and food shops in France, and beyond.

You might not think they’re such a bargain (the wholesale price of the truffles is currently between €600-€900, or $825-$1250 per kilo, 2.2 pounds), and with retailers like Dean & DeLuca selling black truffles for $200 per ounce, one might be tempted to stock up. But unless you have a resale license, you need to get in line with everyone else.

Luckily, Madame Gaillard took a shine to me and invited us to her casual, but chic ‘truffle-bar’ restaurant in Cahors, for dinner with her kids (and a few “friends” that showed up, coincidentally, at around the same time the truffles started to get shaved), so I’d have a chance to indulge.

Interestingly, the appeal of truffles isn’t so much their taste. It’s their aroma that makes you wilt with pleasure. As you might know, a good portion of taste relates to the scent of foods. If you don’t believe me, next time you’re eating something, hold your nose and see how your perception of it changes. Although you might want to do that at home; if you do it in a French restaurant, the chef might toss you out.

Thankfully there was no danger of getting tossed out of Henras, and no need to hold my nose at anything they put before me, either. As I was waiting for dinner, sipping a glass of the black wine of Cahors, Madame Gaillard plucked a knobbly, odd-shaped specimen from a bag and quickly shaved it on a plate, adding only a flurry of fleur de sel, before passing it around for us to taste.

They were fairly tasty but only faintly flavorful: the pleasure was from the scent wafting upward from the plate, not from what I was chewing on. And that was when I saw the folly of those people making things like “truffle burgers” using over-sized slices of truffles, and sandwiching them between a bun.

It’s kind of ‘daredevil dining’ and is all about machismo than really looking to get the best out of the truffle (kind of like eating a vanilla bean versus using it in a sauce) but for the rest of us, a few slices shaved over pasta or risotto is simply heaven. Or sliced and served atop toasts smeared with salted butter.

Not from the region, be equally unforgettable and luxurious, was the absolutely gorgeous plate of Spanish Iberico ham, made from the meat of pigs which feed on wild acorns. If you haven’t had it, it’s definitely worth tipping the balance of your carbon footprint to get yourself to somewhere that’s it available.

I’m not one of those people that thinks “Fat is flavor!” no matter what. But when you slip a piece of this in your mouth and it simply melts away, everything else stops momentarily and you realize you’re eating something extremely special. I’ve seen some of my compatriots in Spain, yanking off the thin ribbon of fat and leaving it behind, startling the nearby Spaniards, and me. Then the chef got to work scrambling eggs.

Lest you think scrambled eggs are boring, or just breakfast fare, they shaved an entire truffle (at least) into the eggs before the chef, with his slow-moving spatula, coaxed the eggs over the lowest possible heat until they firmed up. But just ever-so-slightly, and were served runny and aromatic. I wouldn’t mind them for breakfast every day.

Like, for the rest of my life.

As he was piling the eggs onto my plate, the chef remarked, “You can’t serve this in America”, assuming he was talking about the astounding amount of black truffles in the dish. But he was referring to the softly-cooked eggs. Can you really not serve soft-cooked eggs in America anymore? People, get thee to a farmer’s market and buy your eggs from a trusted source.

(And I didn’t quite know where to put this picture of the truffle brush that looks exactly like a truffle, so it’s here just because I loved it. I would’ve bought it, but think they might have flipped if they knew I was going to use it to scrub pots and pans.)

Our meal continued through a few more truffle-laden courses, including a firm, jellied aspic, molded with a disk of foie gras from a local producer, slices of black truffles, and artichokes.

But eventually, the last truffle was shaved, the red wine was polished off, our glasses of mousse au chocolat (sans truffes) were scraped clean, and it was time to call it a night.

It was a fantastic experience at Henras. And aside from all the truffles that were added to my tally, also added were a few more words to my French vocabulary.

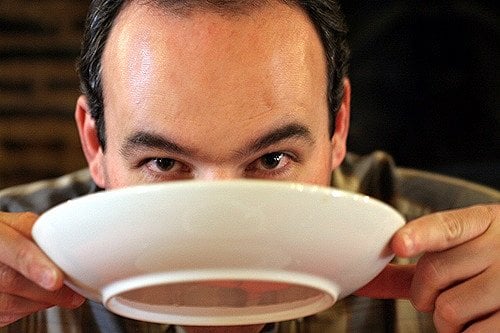

One, which was particular to this region, was chabrot: the pouring of red wine into one’s almost-finished bowl of soup, which is lifted up and polished off. And like the bowls of wine-enriched soup that kept us warm and fortified as we journeyed through the vineyards and restaurants of the Lot, I wasn’t looking forward to the end.

(Next up….the final post from Cahors)

Related Posts

The Truffle Market at Lalbenque

Henras Truffles

Restaurant

40, bis boulevard Gambetta

Tél: 05 65 23 74 06

Laboratoire

284, rue Wilson

Tél: 05 65 35 20 22

The restaurant is in downtown Cahors. The laboratoire isn’t open to the public, although you can buy their products there as well as at the address on boulevard Gambetta.