Raclette

Sometimes you wonder if people do eat all the stuff we think they eat in other countries. Do Russian people really eat blini and follow them up with shots of iced vodka? In Hawaii, are people sitting around dipping their fingers into bowls of poi? Do Americans actually eat the skins of potatoes? How many Parisians actually nibble on macarons? And is it so that Swiss people eat copious amounts of melted cheese, stirred around in pots and heaped on plates?

People in Switzerland actually do eat Fondue and Raclette, as I found out on a recent visit. But eating Raclette outside of Switzerland is like eating a New York hot dog anywhere but standing on a crowded sidewalk in New York. Sure you can do it, but it’s not as much fun. (And somehow never tastes as good.)

I first heard about Raclette a few decades ago when I was working in Berkeley, and since I’m attracted to rituals involving food, when I found out the chef’s girlfriend was Swiss, I, and my co-worker Linda, started hounding her to invite us over for a melted Swiss cheese-fest.

“Oh, no! You can’t just eat raclette anywhere or anytime. You have to be in the mood, sitting by a beeg fireplace, ready to make love with someone…” she said, with grand sweepings gesture of her arms and voice trailing off, evidently with thoughts of gettin’ down by the hearth. Although I had a lot of fun with my co-workers, my idea of an exciting time with them didn’t involve melted cheese. (There were a few incidents involving too much Zinfandel, however. But let’s not get in to those now.)

At Caveau des Vignerons in Montreux, I was having dinner in their rustic dining room all by my lonesome, not feeling very romantic, and saw on the menu Swiss specialties like Fondue and Raclette. But since both required a minimum of two people to order them—which is odd because I think I could eat a double-order of anything with melted Swiss cheese on my own—I realized that I had to order something else.

Unfortunately as soon as I had walked into the dining room, the smell of sizzling cheese wafting through the air had hit me and by the time I polished off my enormous plate of Veal Zürichoise with rösti (crisp shredded potato cake, which kinda made up for the lack of sizzling fried cheese) a tiny tear began making its way down my cheek as I watched the other diners, paired off in happy couples, feasting on Raclette.

I don’t know how she noticed it, but the woman making the raclettes and bringing them right over to the other tables came by and didn’t offer me a tissue to dry my tears, but instead asked me if I’d like to try a Raclette on my own. I expressed disappointment that it was only available for a minimum of two people and she said, “I will make you one and it’s not a problem. It would be my pleasure.”

Even though I was pretty stuffed from finishing off a pile of veal and potatoes, I made a nosedive into the lump of gooey melted cheese she set down before me, which was gone in seconds. She came by and offered more, which I begged off, but I started talking to her and found out she was the Gloria in “Chez Gloria“, the nickname of the restaurant, and I asked her if I could stop by the following day for a lesson in making Raclette.

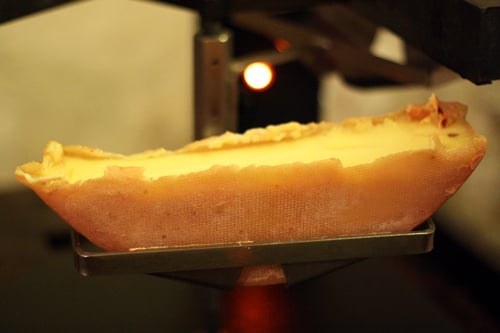

Of course, making Raclette by the open fire is the ideal way to prepare Raclette (although I can’t say if it’s effective foreplay, because I signed a confidentiality agreement) and there are a variety of raclette makers intended for home use. Not everyone wants to splurge on a professional-style raclette grill but I do know that cheese shops in America often rent them out so you can give it a try at home.

Aside from the vehicle for melting the cheese, one uses a flat-edged spatula to scrape the layer of melted cheese off the wheel and onto the plate. I’ve seen wooden ones but I love the professional Raclette knives, and even though I would probably only use it a few times, I am putting one at the top of my Christmas wish list.

The first thing to do before making Raclette is close the doors. When I was sitting in the Caveau de Vignerons, as soon as Gloria started firing up the cheese melter, she walked over and shut the large wooden doors that led up to the bar. Which I thought was funny because I was sure that that locals, who sit on what have the be the most welcoming place to park your backside in Switzerland, wouldn’t be enticed by the smell of sizzling cheese as much as I was.

Another point that I’d like to make is that white wine goes better with most cheeses than red. I know, I know…there are folks who disagree and that’s fine; if you want to drink red wine with Raclette or cheese, well, go ahead. But the fruity, dry (and some say ‘sour’) white wines of the region made from Chassela grapes, are often sharp and minerally, making them the ideal wines to accompany—but not overwhelm—both mild and strong cheeses. So please stop pushing me to drink red wine with cheese; I don’t want it.

I switched to drinking white wine a few years ago because I find that I can pick up a lot of the subtleties in white wine better than in a glass of husky red wine. Of course, that’s a broad generalization but I just find white wines more interested nowadays, more drinkable, and I also don’t feel so dull-headed the next morning if I drink a little more than I should.

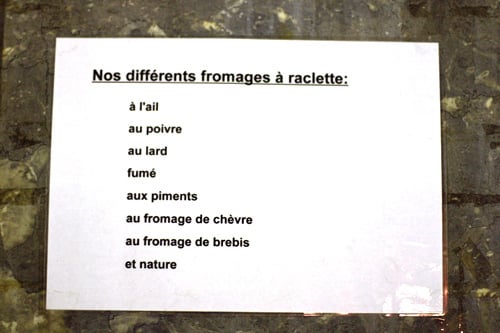

It should go without saying that Raclette should be made with Raclette cheese. Interestingly, a local cheese shop was advertising cheese with various flavors, and when I did a little searching online, I found that versions of Raclette cheese are made everywhere, from Michigan to Australia and New Zealand. I haven’t tried them, but it’s nice to know that you can make Raclette in a whole lotta different places, not just in Switzerland.

But no matter where you live, the method of making Raclette is the same: Heat a large half or wedge of Raclette cheese under a very hot heating element or a broiler, or by an open fire, until the surface is melted and beginning to form a firm skin on it (which is the way I like it.) Once it’s gooey and melted, use a spatula or the back of a large knife to scrape the cheese onto a warm plate.

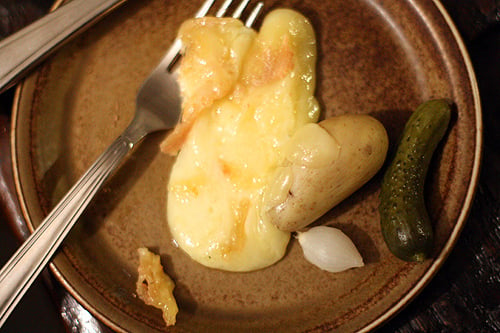

Traditional accompaniments are cornichons (tiny pickles), roasted new or fingerling potatoes, and pickled onions. There’s some discussion whether you should peel the potatoes or not. I always eat the skins but remember quite a while back when I was in Germany and I started eating the skin on the potatoes and the other diners at my table were openly horrified at what a rube they were dining with. I don’t know if that’s changed but I’ve yet to see any restaurants in Europe offering fried potato skins. At Caveau de Vignerons, they serve the potatoes in the skins on and I wasn’t picking it off. So perhaps the Europeans and the Swiss have gotten with the program.

I’ve also read that meat such as ham or viande des Grisons, very thin slices of lean air-dried beef, is sometimes served alongside Raclette. But I’ve never seen it presented that way. (Which doesn’t mean you can’t eat it that way, it’s just that I’ve never seen it. So you can do what you want.)

Personally, I’m not planning on buying a Raclette maker. But this winter, I’m hoping for a chance to go skiing in the alps. Since it’s been a while, I’ll probably spend most of my time warming myself around the fire while everyone else hits the slopes. And to keep me company, I might bring along a sack of potatoes, some pickles and onions, and perhaps sneak in a little bit of meat, and find a big hunk—of cheese—and have a good time all by ourselves around a roaring fire.

Caveau des Vignerons

“Chez Gloria”

rue Industrielle 30bis

Montreux, Switzerland

Tél: 021 963 25 70

Related Links and Recipes

Raclette, No Fancy Equipment Needed (Comestibles)

Raclette (Swiss World)

Swiss Raclette (FX Cuisine)

Traditional Raclette (Switzerland-Cheese)

Firing up a raclette feast (Houston Chronicle)

Raclette (Wikipedia)

Raclette Mac & Cheese (Lara Ferroni)