Blacker Berry Galette

My Netflix queue has gotten out of control and is entirely too long. And to make matters worse, I keep adding to it. Being out of the U.S. for so long, I missed watching binge-worthy, must-watch classics like The Wire and Breaking Bad when they came out, and I’d love to sit down on the sofa for another few months and watch them now that they are streaming, as well as rewatch all five seasons of Six Feet Under, which was one of the best shows that’s even been on television. How they managed to make a show about death so human is beyond me, with a finale that’s lauded as the best ending for a television series ever. Which also made me wonder how they could have left the end of The Sopranos, another incredible show, land with such a thud?

My Netflix queue has gotten out of control and is entirely too long. And to make matters worse, I keep adding to it. Being out of the U.S. for so long, I missed watching binge-worthy, must-watch classics like The Wire and Breaking Bad when they came out, and I’d love to sit down on the sofa for another few months and watch them now that they are streaming, as well as rewatch all five seasons of Six Feet Under, which was one of the best shows that’s even been on television. How they managed to make a show about death so human is beyond me, with a finale that’s lauded as the best ending for a television series ever. Which also made me wonder how they could have left the end of The Sopranos, another incredible show, land with such a thud?

The pandemic and confinements were certainly good for whittling down those “Watch Lists” but one show that jumped to the top of the queue was High on the Hog. It’s an eye-opening, unnerving, and emotionally difficult look at the role that African-Americans, who were brought to America as slaves, had in shaping American cooking. The subtitle of the show is “How African-American Cuisine Transformed America” which sounds like a big bill to fill, but the four-episode show traces how that happened.

And lest anyone doubt the rich contribution African-Americans have made to our cooking, author and Cook’s Country editor Toni Tipton-Martin pointed out in the program that Black Americans have been used by food brands for decades in America to denote quality, by brands like Aunt Jemima and Uncle Ben, which gave host Stephen Satterfield pause as well, flipping the narrative about those culinary characters (or caricatures) that many of us grew up with.

I was especially interested in the story of James Hemings, Thomas Jefferson’s chef. We often use an apostrophe in English to denote “ownership” (i.e.; “Jefferson’s) which is especially key here as his chef was also his slave. Jefferson took him to France to learn to cook in 1784, and he came back, creating and interpreting dishes and influencing generations of American cooks of all colors and origins. We have James Hemings to thank, along with his brother Peter, for dishes like French fries and Macaroni and Cheese (that latter of which was influenced by his training in French cooking in Paris), who James trained as a cook as part of a deal that he made with Thomas Jefferson in exchange for his freedom. The least we can do for the man who gave us French fries in America is to put him on a coin. Don’t you think?

Although I’m not Black, as an American, I feel cheated that we were presented and taught an incomplete and inaccurate facet of our history. As a cook and a baker, I’m startled (as well as grateful) to learn about Hemings’ (and Hercules Posey, George Washington’s influential cook, who was also a slave) invaluable contributions to our nation’s culinary identity.

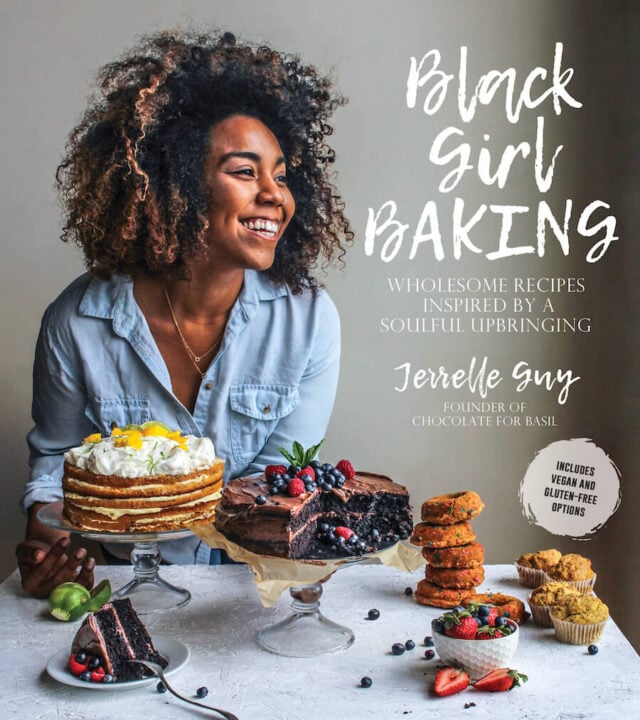

Several Black contemporary cooks, bakers, and pitmasters are featured in the show who are carrying on the traditions of their ancestors. One is Jerrelle Guy, author of Black Girl Baking: Wholesome Recipes Inspired by a Soulful Upbringing. I’m going to go out on a limb here and say that I don’t think I’ve ever seen a more joyful-looking author on the cover of a book than Jerrelle is on hers. (If only I could grow my hair out like hers, I might finally get my mug on my next book cover.)

Most of Jerrell’s recipes have vegan, dairy-free, and egg-free options, so the recipes in her book are accessible to people with those concerns. But since we are in full-on cherry and berry season, her Blacker Berry Crostata had the most appeal to me.

I’ve seen galettes go from unknown, to online memes. Sometimes they’re called crostatas, other times they can be called tarts. In France, open-face fruit tarts are usually called tartes, but I’m using ‘galette’ here because that’s what everyone else is doing elsewhere, and I don’t want to be left out. Because French home ovens tend to be smaller than their U.S. counterparts, it’s usually not possible to fit an 11″ x 17″ baking sheet in one, the size that’s standard in the States (referred to in professional kitchens as a half-sheet pan), I had to spring for a larger oven to use my American half-sheet pans in.

So home bakers tend to use tart molds, and not the kind with removable bottoms, which is sort of a blessing as you don’t have juices overflowing in your oven or burning on your baking sheet, even though they get more Likes on Instagram. The tart molds in France that are most commonly used are like the one above. T-Fal is a name-brand that makes one, although you can pick one up without name or label for around €3 at any vendor that sells articles pour la cuisine at most of the outdoor markets. I don’t know where to get them outside of France but you can find fluted porcelain tart dishes or glass tart molds, and some people use shallow cake pans or cast-iron skillets as stand-ins for baking dishes. But you can use a baking sheet lined with parchment paper, which is what I often go with.

Whatever you use, I think you’ll be as happy with this tart, or crostata, or galette, as we were, especially if you top it with a scoop of vanilla ice cream. But served on its own, it’s no slouch either.

Blacker Berry Galette

For the crust

- 1 cup (140g) all-purpose flour

- 1/4 cup (35g) whole wheat flour, (or use 1 1/4 cups, total, all purpose flour)

- 1 teaspoon kosher or sea salt

- 7 tablespoons (3 1/2 oz, 100g) unsalted butter, cubed and chilled

- 6-7 tablespoons (90-105g) sour cream or plain full-fat yogurt

For the berry filling

- 2 cups (265g) blackberries, halved

- 2 cups (280g) pitted sweet cherries, halved (pitted weight)

- 2 tablespoons dark brown sugar

- 2 tablespoons all-purpose flour

- 1/2 teaspoon vanilla extract

- 2 teaspoons crème de cassis, or 1 teaspoon orange liqueur (optional)

- zest of one lemon

- 2 teaspoons freshly squeezed lemon juice

To make the dough

- Put the flour(s) and salt in the bowl of a stand mixer fitted with the paddle attachment, or in a medium bowl if using a pastry blender or another tool to make the dough by hand. (You can also use a food processor.) Add the chilled butter and mix at medium-low speed until the butter is in pieces the size of chickpeas.

- Add 6 tablespoons (90g) of sour cream or yogurt and continue to mix the dough until it starts coming together. I like stop the machine and use my hand to mix and feel the dough, rather than finish it in the machine (since overmixing can make the dough tough), then gather and gently knead the dough into a disk. If it's too dry to shape into a disk, add the additional 1 tablespoon (15g) of sour cream or yogurt. Wrap the dough and chill it thoroughly, at least 1 hour. (It can be made up to 2 days ahead and stored in the refrigerator.)

To make and assemble the tart

- Either line a baking sheet with parchment paper or have a 9- to 10-inch (23cm) tart mold or dish ready, one that doesn't have a removable bottom. (If yours does have a removable bottom, I advise baking the tart on a parchment lined baking sheet in case of any drips.) Preheat the oven to 425ºF (220ºC).

- On a lightly floured surface, roll the dough into a 13-inch (33cm) round. If it cracks around the edges when you start to roll it, pick up the dough, hold it perpendicular to the counter, and gently pound the edges on the counter as you turn it, to make the edges more malleable. Then continue to roll the dough into a circle. Transfer the dough into the baking dish or onto the baking sheet.

- Mix the blackberries, cherries, brown sugar, flour, vanilla, crème de cassis or orange liqueur (if using), lemon zest and juice in a bowl.

- Distribute the berry filling over the dough, leaving a couple of inches (~5cm) of space around it (if using a baking sheet), which you can now fold the dough over the berries to create the crust. Brush the top edges of the dough with melted butter and sprinkle with large-grain or granulated sugar.

- Bake for 25 minutes, or until the berries are cooked through and bubbling, and the dough is nicely browned. Let the tart cool for a few minutes if it's on a sheet pan, then slide the tart onto a cooling rack, which is easier if using a flat baking sheet. (A rimmed one might require a bit of finesse, but I do it all the time and I know you can do it too.) If using a baking dish and it's sticking and not coming out easily, you can let it cool in the pan. Mine is non-stick so comes out easily.

Notes

*Every spring I eye the cherry pitter in my kitchen drawer with the great anticipation of using it when cherry season arrives. Often when I show it or talk about pitting cherries, it inspires people to tell me that one can use a bobby pin to pit cherries. Or a straw or a cork with a hook in it or a bottle with a chopstick, or something else. I’ve pitted thousands of cherries in my life and this is one of the few single-use items in my kitchen, like my coffee pot (and toaster), that improves my life. I’m a fan of the Oxo cherry pitter with the Westmark coming in second, and wrote more about why a cherry pitter is a worthwhile kitchen tool in a recent newsletter titled, Go ahead, treat yourself to a cherry pitter. (It went out to paid subscribers, but the gist of it is what I said, just above.) But if you’d rather stick with fishing the pits out with a hairpin, you’re welcome to :)