Apple Crunch Tart

One of the things I keep vowing to do is to read more books. It’s hard when I’m at home, where there are many other things beckoning for my attention. But when I go on vacation, I bring a few books along and find a good chair to park myself in as much as possible. It helps that internet is either non-existent, or the connection to it is poor, out in the countryside, where some of my friends don’t even have WiFi at home. It drives me nuts for the first few hours, then I ease into it and relax knowing that the rest of the world can wait, while I envelope myself in a good read.

I find myself drawn to memoirs, especially culinary ones as I can relate to the characters. Some are beautifully expressed and written, such as Toast by Nigel Slater, 32 Yolks by Eric Ripert, Notes from a Young Black Chef by Kwame Onwuachi, and The Apprentice by Jacques Pépin, which I just finished.

Memoirs are tough to write. (Trust me.) It’s a challenge to open yourself up completely and while most chefs have had some difficulties in their life, back in 2003, when Jacques Pépin wrote The Apprentice: My Life in the Kitchen, it wasn’t the norm to be so frank, especially from someone as universally beloved as he is. Recent culinary histories have cast food icons in a different, and sometimes less-flattering light than we may know them, so it’s interesting when someone writes their own story, which allows them to acknowledge both the good and the bad, and the ups and downs, in their own words.

In his memoir, Jacques Pépin doesn’t shy away from his difficulties. Cruel chefs, a near-fatal car accident, his close friend Craig Claiborne’s downfall in the aftermath of a painful memoir about his childhood abuse which was poorly received by the public, launching a restaurant that closed after six months (it was successful but his wife, Gloria, had had enough…), and more. Jacques arrived in America in 1959 speaking no English and went on to nearly getting his PhD from Columbia University and writing dozens of cookbooks, several of which are considered seminal books on cooking, especially those that focus on French techniques, which he is the master of.

He isn’t well-known in France and Romain didn’t know who he was when he met him a few years ago at an event in New York, but they hit it off. Coming from France, Jacques talks in his book about how people were strict about how food could be prepared (and what time it was served), and he appreciated that Americans didn’t have so many rules when it came to cooking and eating. All that mattered in America, he says in his book, was that something tasted good, and that “people were willing to try items that lay outside their normal range of tastes.” Back home, “unless a dish wasn’t prepared exactly ‘right,’ people would know and complain.” If you added something like carrots to bœuf bourguignon (which he notes “are great” in it), people would call for the guillotine. That was before online shaming, so at least he dodged a few bullets there.

Jacques was also ahead of his time as he wrote back in 2003, about how Black people have been noticeably absent from the four-decade “culinary revolution” that took place in America. He recalls walking into a kitchen in New York and finding himself being the only person who wasn’t Black, and the crew eyed the guy with the funny accent with suspicion. But as soon as the rush of work started, he dove right in alongside them and was accepted, and as a fully-trained French chef, he was impressed by how hard and how well they worked. He also began frequenting butcher shops in Harlem which were the only places in Manhattan where he could find some of the lesser-used cuts of meat that he was used to eating in France. He noted that American cuisine was “poorer for” not acknowledging, accepting, and including, the contributions of Black cooks into our culinary legacy as much as they should be for their contribution to it.

Jacques says he is no longer a “French” chef since he has lived in America for so long, and has adopted a more American freestyle of cooking, but still relies on French techniques. If you’ve ever seen Jacques Pépin cook anything on television or in person, you know he can do almost anything. (But if you think it’s easy to lose your native accent, he’s been in the U.S. for nearly sixty years and still speaks English with a very present French accent.) If I had to choose, the two-volume The Art of Cooking are arguably his best. When he came to work with us at Chez Panisse shortly after they were published, we were already fans and he toggled back and forth between the regular kitchen and the pastry department.

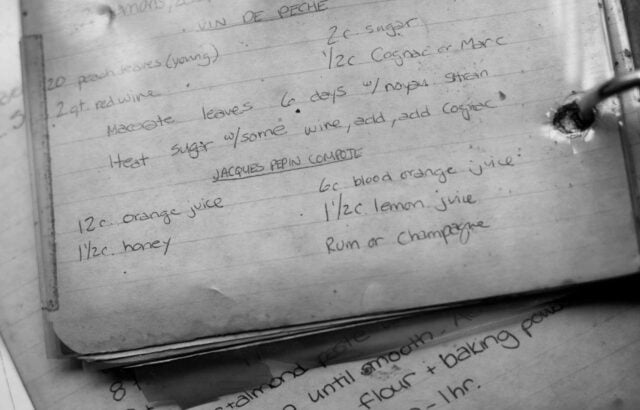

I still remember the fruit salad he made, using the recipe (above) that I found I’d written down in my old recipe book, and we watched, fascinated, as he carved an ornate basket out of a whole watermelon to serve it in. It’s wasn’t very Chez Panisse, but we loved it.

He also made a lovely, well-decorated chocolate cake to serve in the café for dinner one night. He was so proud of that cake, which was absolutely gorgeous…but I didn’t have the heart to tell him that we needed six more cakes to get through an evening’s service. (Of course, that one cake sold out immediately.) And he made Apple Crunch tarts from The Art of Cooking. My history may be off, but in the late 80s, few knew what a fruit galette was. There were no viral posts or Tik Toks montages of galettes bubbling away with irregular sugary edges folded up and over the fruit. Once people realized they were easier than pie, it’s easy to understand why they took off in popularity.

Back then, the dough he showed us how to make for the Apple Crunch tarts was super simple. Eventually, the top layer came off and we started making galettes. And that was that.

I decided to revisit the Apple Crunch tart, a marriage of French and American cuisine; flaky dough filled with apples, which reminds one of Apple Pie, with a bit of French flair from the freeform crust. Jacques noted in The Apprentice that he “actually feels ill when he sees food being wasted” and in that spirit, I picked up some pommes à cuire, or “cooking apples” at the market, that are sold for a better price due to a few dents and dings. They might ruin a photo but I find them attractive and that’s what apples actually look like.

At Chez Panisse we peeled a lot of apples. An intern once arrived for a tryout and in the middle of peeling their first case, they said, “This is boring.” Peeling apples might not be the most exciting thing bakers do, but it’s part of the job and in the fall and winter, we peeled a lot of apples.

In the pastry department, one day we had a tasting of various apples from local farms, with a variety of apples laid out in front of us. Before we tasted any of them, my co-worker Linda picked up the biggest one, a huge apple that was the size of a softball, and said, “I don’t know how these taste, but I like them the best.” So feel free to bake with any apple (of any size) that you like, although for pies and tarts, it’s best to use one that won’t turn to mush when baked.

In France, people often use a mix of apples since each apple has a different flavor and it’s nice to combine them. You will notice there’s not a speck of cinnamon in this tart, which is Jacques’s French side showing, since people feel cinnamon detracts from the pure flavors of the apples. If you want to add a pinch, go ahead, but like Jacques, I like to keep the filling on the French side, and keep the focus on the apples.

Apple Crunch Tart

For the dough

- 2 cups (280g) flour

- 1 teaspoon kosher or flaky sea salt

- 3/4 cup (6oz, 170g) unsalted butter, cubed and chilled

- 1/2 cup (120ml) ice water, plus a tablespoon or two more, if necessary

For the apple filling and assembling the tart

- 1 3/4-2 pounds (800-900g) apples, peeled, cored, and cut in 1/4-inch (.5cm) slices

- 1-2 tablespoons granulated sugar, (use the lesser amount if the apples you are using are sweet)

- 2 1/2 tablespoons (36g) unsalted butter, finely cubed

- 1 egg yolk, mixed with a teaspoon of milk or water

- 2 tablespoons granulated brown sugar, see headnote (optional)

- To make the crust, mix the flour and salt in the bowl of a stand mixer fitted with the paddle attachment. (You can also make this by hand in a mixing bowl using a pastry blender or your hands, or make it in a food processor.) Add the chilled butter and mix until the butter pieces are the size of blueberries. Don't overmix; it should be quite lumpy. Add the ice water and stir until the dough comes together. I find, even if using a stand mixer, that I use the mixer only to mix the water partially in, then do the rest by hand with gentle folding in the mixing bowl, so as not to overwork the dough.

- Divide the dough in two, shape both pieces into disks, and wrap and chill them for at least 30 minutes. (The dough can be made up to two days ahead.)

- To assemble the tart, line a baking sheet with parchment paper or a silicone baking mat. Toss the apple slices with 1 to 2 tablespoons of sugar in a bowl.

- Remove one piece of dough from the refrigerator and roll it out on a lightly floured countertop until it's a 14-inch (36cm) circle. Place the round of dough on the prepared baking sheet. (I fold it in half and work quickly to transfer it then unfold it on the baking sheet, but when I made this with Jacques, he rolled his dough around the rolling pin first, before moving it, and unrolling it on the prepared baking sheet.) Place the apples in an even layer over the dough leaving a 2-inch (5cm) exposed border. Distribute the diced butter bits over the apples. Fold the outside edges of the dough up and over to tuck in the apples.

- Roll the other disk of dough to the same size as the first. Brush the bottom crust that's folded over the apples liberally with water then place the second round of dough over the apples and bottom crust, tucking the edges underneath the bottom of the tart. Place the tart on the baking sheet in the refrigerator or freezer for 15 minutes.

- Preheat the oven to 400ºF (200ºC) and set the rack in the middle of the oven. Mix the egg yolk with the water or milk in a small bowl and brush it over the top of the tart. Sprinkle the granulated brown sugar evenly over the top, cut four slits in the top and bake until the top is well-browned and crunchy. When done, thick apple juices should be bubbling up in the slit holes, indicating they are cooked. The tart should take about 30 to 35 minutes to bake, depending on the apples and your oven. Remove the tart from the oven and let cool a few minutes, then slide onto a wire rack.