The Making of Drinking French

A few years ago, after My Paris Kitchen came out, I began thinking about what I’d write about next. Whenever you have a book come out, the most common question is, “What’s your next book?” Sometimes you already have an idea, but other times, it’s nice to sit back and enjoy what you’ve written. I was happy that people took to that book so much, and after a respite, I started thinking about what to write about next.

Because I was asked about it so much, I decided that telling the story of my apartment renovation would make an interesting book, which turned out to be true, knowing that people would be surprised at what a comedy of errors it turned out to be.

But another subject I found myself becoming more and more interested in was the culture and traditions of French drinkings, and the drinks themselves. I submitted both proposals at once, nearly six years ago, in a two-book arrangement with my publisher, deciding to tackle the renovation story first while it was still fresh in my mind and take on French drinks when I was done. That ended up being a good thing…because I needed a drink after reliving L’Appart…and from what many of you have told me after reading it, so did you!

French friends and people I met during the process of writing Drinking French, gave me curious looks when I told them the subject. Each would stop for a moment, processing the information, having never considered French drinks to be the subject of an entire book, even though French food has been widely explored. before launching into a story about a long-lost French apéritif the previous generation had enjoyed, such as Dubonnet or Suze. When I explained how people in France drink, and what they drink, have such an important role in their culture, and are fascinating to others who come to France to sit in a café and have a coffee, or have a carafe of vin maison (house wine) ordered off a chalkboard on the wall with dinner, every French person I mentioned the project to nodded in approval. So I went all-in.

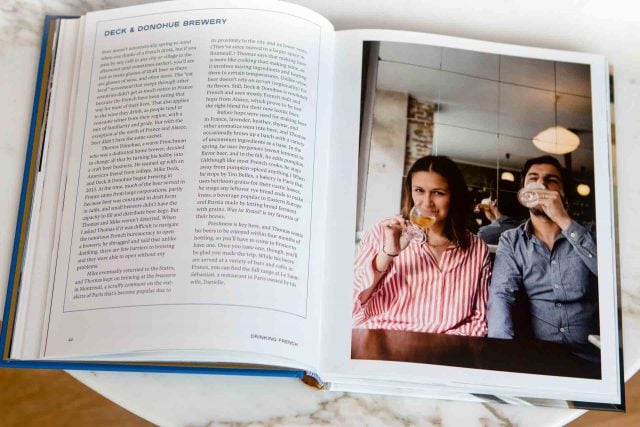

(Thomas Donahue, owner and founder of Deck & Donahue brewery, featured in the book, with his wife Danielle Lavadenz, owner of Le Saint-Sébastien restaurant in Paris.)

I’ve worked with my publisher Ten Speed Press on most of my other books, and was happy to be working with them again. I’ve known some of them for nearly twenty years. They took a chance on my ice cream book, when another editor passed, telling me, “You don’t have a show on Food Network.” The Perfect Scoop has been so successful that they asked me to do a revised and updated edition, which continues to sell very well. (That’s not bragging, but a good reminder that having people pass on your work isn’t always a bad thing, and that it’s also good to be loyal to the people that help you out.)

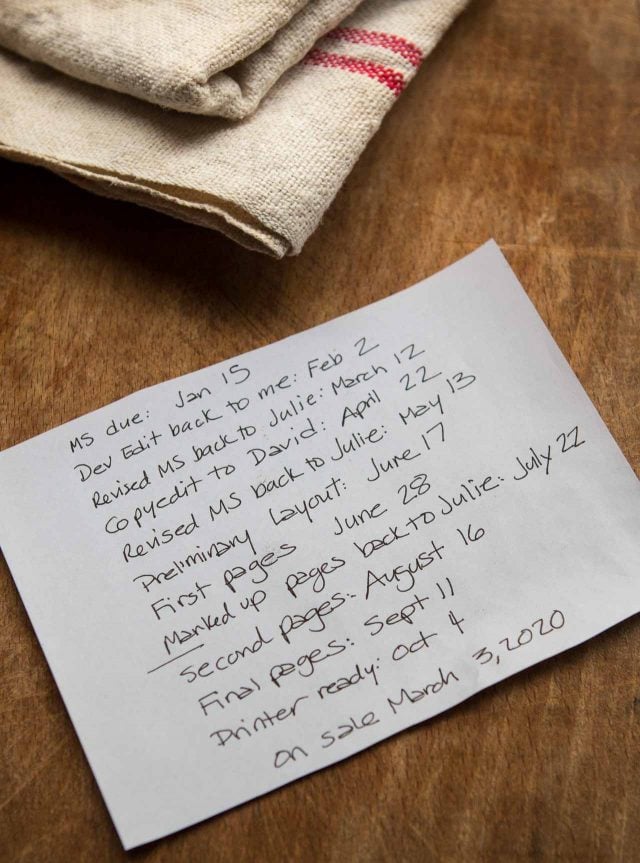

After they reviewed my sample chapters, a list of places I wanted to profile to help tell the story, and a list of the recipes, my editor, Julie, sent me a timeline for the book, aka: There goes my summer vacation…

I decide the best way to start the book was as a typical day starts in France, which is with breakfast at home, sipping a café au lait, or in a café, drinking a café crème or café express at the bar. Since I’m not a morning person, I’m invariably in my kitchen and kick things off with my Café au lait (page 8). But I couldn’t resist making a note in the book about presumably well-meaning people correct others, who use the French name for a short black coffee, which is indeed an express, (or expresso) also called a café noir or un p’tit noir.

When lunchtime rolls around, a glass of wine might be enjoyed with the plat du jour, even as la Coca, or Coca light or Coca zéro, have been making inroads. Throughout the day, people stop into their local café to sit with friends and sip a Limonade (page 36), a Citron pressé (page 33) or a colorful minty Menthe à l’eau or grenade (page 37) made with red pomegranate syrup. And yes, I’ve included recipes for homemade Fresh Mint syrup (page 272) and Pomegranate syrup (page 274) in the book, so you can make them at home if you want to skip (or can’t find) store-bought syrups.

(There’s also a story that, for space reasons, I had to trim from the book: I originally thought the drink was called a menthalo, which is how menthe à l’eau, is pronounced. Spoken French doesn’t always correspond, phonetically, with written French, so I spent a considerable amount of time digging for more information about the elusive menthalo…and couldn’t understand why I kept coming up with nothing in books or online.)

Being France (and being me), chocolate needed to be well-represented in the book, too. So in addition to steaming glasses of Vin chaud (mulled wine, page 26) that are offered up in cafés to mitigate the chill of winter, I included three different hot chocolate recipes (pages 13-16), because it was hard to stop at just one.

The first is a traditional, rich, thick Parisian Hot Chocolate, the kind that’s so thick you have to tip your head all the way back to get that last gulp lining the bottom of the cup. Of the two others, one is a version of a Spiced Hot Chocolate that I enjoyed at a pastry shop in the Marais while working on the book, which, as soon as I tasted it, immediately made me realize that I had to include it in the book.

The other was my long-lost Salted Butter Caramel Hot Chocolate, which I tried to make into a handy mix that people could make at home many years ago, with a friend whose family harvests salt in Brittany. But I couldn’t accurately recreate it in a powdered form, so here it is – in the book! – as are the Armagnac marshmallows shown that are floating in the hot chocolate at the beginning of this post. How could I present three hot chocolate recipes but no marshmallow? That would be mean.

For spring and summer, I’ve got you covered with a trio of icy Frappés (pages 27-30.) Two are bolstered with coffee and chocolate (above), and the third is an adults-only frappé, with just a wee shot of Bay-lèze, from our friends in Ireland, whose liqueur I learned is surprisingly popular in France.

Later in the day, as evening rolls around, beer and wine become the drink of choice. Or perhaps a cocktail before dinner, finishing off the evening with a digestive such cognac or Armagnac, two of France’s best-known spirits. However there are a number of French drinks that are less familiar, such as eau-de-vie, crystal-clear distillations of fruits, vegetables, and even roots. On a trip to Dijon to visit Vedrenne, to learn how they make their fruit syrups and spirits, I met Matt Sabbagh, one the last traveling distillers in France, who distills eau-de-vie on the back of a truck, which he ages into Marc de Bourgogne and Fin de Bourgogne, two nearly-forgotten spirits that he is not only hoping to keep alive – but he wants to see them thrive. I was captivated by what he was doing out there in a cold field in Burgundy, where we met.

Wherever he parks his alembic still, in village squares or out in the countryside, locals bring him whatever they’ve grown in their gardens and yards, to distill into eau-de-vie. Matt just started making gin as well, used to make the newly popular Gin To (gin & tonic), which is threatening to replace the Aperol Spritz (which replaced the Mojito) as the trendy drink of choice in France.

But if you’re a fan of the Spritz, as I am, there’s a recipe for a Corsican Cap Corse Spritz (page 108), a Tangerine Spritz (page 66), as well as a spritzy, grapefruit-based Suze in Paradise from Quentin Chapus of the Fédération Française de l’Apéro. So if you’re a fan of French apéritifs, as I am, you’ll find a whole chapter filled with dozens of classic and contemporary French apéro recipes.

Matt also made me a terrific lunch out in the wild of duck confit, cooked on his boiling-hot still, which we feasted on in the breezy hills outside of Beaune, with local white wine, baguettes, and charcuterie. What a day that was! How could I not feature Matt in the book?

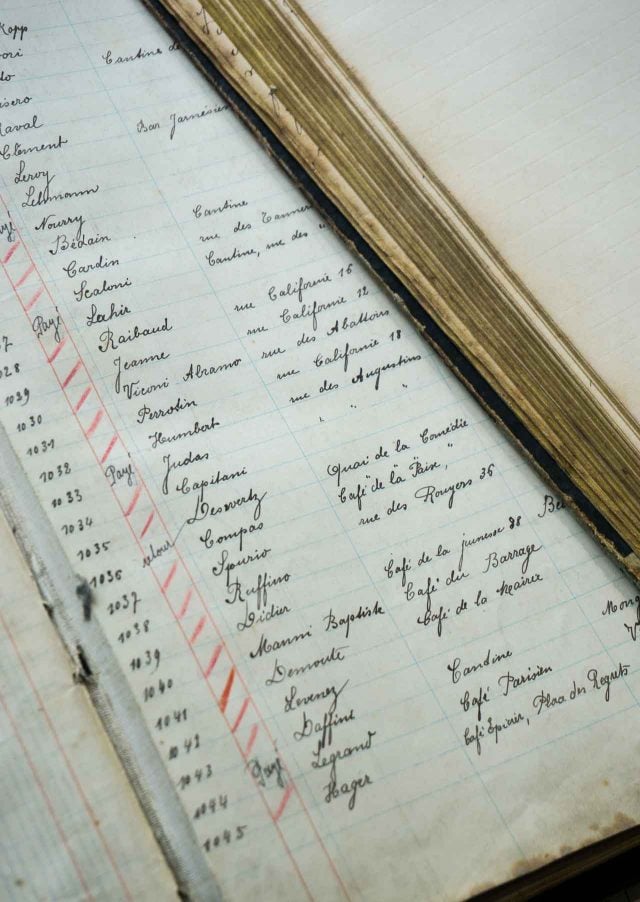

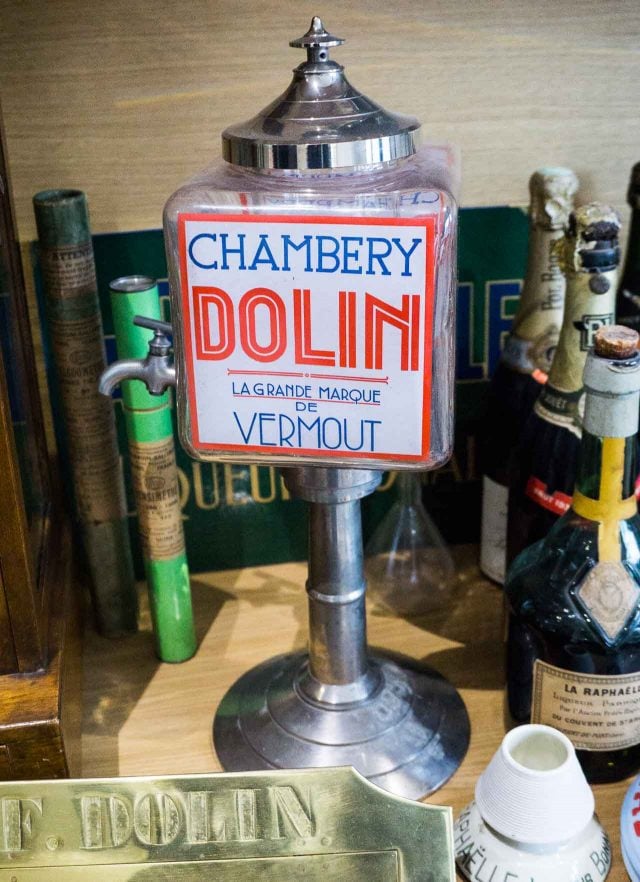

Elsewhere in France, I hit the road, winding my way up the alps, riding trains, and lolling around the Mediterranean, to discover the backgrounds of some of the most enduring French spirits and apéritifs. Certainly one of the most famous is Dolin vermouth and Pierre-Olivier Rousseaux, whose family owns the distillery, showed me how they make the world-famous dry French vermouth, known as vermouth de Chambéry.

Not only did he show me the vintage bottles they’ve collected over the years, he also shared with me their recipes too. Smitten with the handwritten ledgers (below), I asked if I could take a photo. Uncharacteristically for a spirit-maker, he said, “Sure! What are you going to do? Start a vermouth company?” So I did.

For the record, I have no plans to make or market my own vermouth, save for the French vermouth recipe which is on page 129 in Drinking French, in case you want to give it a go. Just don’t tell anyone I told you to do so.

Many French spirits have a long affiliation with the United States, cemented by prohibition, which pushed Americans looking for a drink to head to France, where a number of classic cocktails were born, such as the Sidecar, the Bloody Mary, and my favorite, the Boulevardier. They’re all in the cocktail chapter, which kept growing and growing and growing. At one point, my editor reminded me that there were only around sixteen cocktail recipes in my original proposal. So even though books are slotted (and priced) according to size, she gave me the go-ahead to include them all. So be ready to drink up, folks.

Dolin vermouth has had an extra-special affiliation with America, and helpfully came up with a non-alcoholic vermouth to ship to the States during the years when the eighteenth amendment went into effect. While Dolin was founded by a botanist, Joseph Chavasse, his daughter Marie Dolin (her married name) was the one who eventually took control of the company and successfully ran it for many years. After explaining that bit of history to me, Pierre-Olivier thought about it for a moment, then told me that for most of its existence, Dolin has been a woman-run company. Vive la vermouth!

Dolin eventually took over production of Bonal, a quinine-based apéritif that was formulated nearby, whose labels reflect the botanicals used to make the drink (below), although in some cases, there’s a key used, as the drink had once been promoted in France as the “key” to opening up your appetite, which apéritifs are thought to do. The French word apéritif comes from the Latin word aperire, which means to “open up,” although we chuckled at how rules have changed and you can’t allude to liquor having any sort of healing quality anymore, but it’s still okay to say À votre santé!…or, To your health!, when lifting a drink and toasting others. After all, we’re not savages.

Looking at all the bottles on the shelves at the Dolin distillery fueled an obsession of mine with vintage labels and spirits bottles while working on the book, and made me realize that, like many things in France, a bottle of liquor isn’t just something to drink – there’s invariably a very interesting, and often long, history behind it. I wanted to share those in the book so I profiled the most popular French liqueurs and apéritifs with vignettes throughout the book about what they are, how they’re made, where they came from, and what’s the best way to enjoy them.

I don’t know of any liqueur whose history is longer, and more interesting, than that of Chartreuse. The liqueur is around four hundred years old, but the Carthusian monks who make it started their journey nearly a thousand years ago.

Much has happened since my last visit twenty years ago to Voiron, where Chartreuse is made, including a new distillery built in the mountains on the same site where one of their previous distilleries had burned to the ground. In addition to facing the wrath of neighbors and natural disasters that destroyed their work, the monks of Chartreuse were also expelled from France, heading across the border into Tarragonia (Spain), where they continued to distill their liqueur until they were allowed to return to France.

In the last few years, as waves of cocktail culture continued to sweep across the world, including in America, Chartreuse became an almost cult-like liqueur/obsession. I use it in baking, for roasting figs and making chocolate soufflés, but until this visit, I never knew that Chartreuse was once a toothpaste (dentifrice.) Talk about an incentive for brushing your teeth!

At one point the French government demanded the recipe for Chartreuse, which the monks were forced to comply with. Fortunately it was returned to them with a note that the recipe was “too complicated.” It was a fortuitous stroke of luck for them, as only two monks guard the secret recipe to this day, so no one else can produce it.

While our friends in Italy are given credit for inventing vermouth (although similar herb-infused wines were previously made in Greece), Noilly Prat is considered the first French vermouth, which is barrel-aged outdoors to replicate the oxidation and evaporation that the wines originally went through as they traveled in barrels from the vineyards in Spain on boats, before other ways to transport the wines came into use.

Times have changed, but they still let the wine mellow outside for months to make their popular vermouth. I visited during the winter when things were overcast, quiet, and cool, and enjoyed oysters by the Mediterranean, along with tastes of the various vermouths Noilly Prat makes. I also stayed in one of the best guest houses in France, with two of the nicest hosts I’ve ever met. One (vermouth) is extra-dry, created for the American market, a since we like our Martinis (pages 97, 157, and 207) cold, crisp, and clear. But I also tasted Ambré vermouth, made with saffron and rose petals, which for a while was only available at the distillery.

Before I left, not only did I stock up on a few things at the gift shop, but the in-residence bartender shared her recipe for a Bloody Mary (page 221) with me, which she fortified with a shot of vermouth to smooth things out.

Three trains, a bus, and a sprint around a forest led me to Les Caves Byrrh (slightly out of breath) in Thuirs, home of the world’s largest wine aging barrel, and lots of other ones, holding wines to make their Grand Quinquina, a ruby-red quinine-based apéritif with a funny name.

There’s no beer in Byrrh and the name was just sort of a fluke. Part of their legacy is a collection of vintage posters on display at their facility. I could have looked at those all day. But had to move on, to a tasting…

In addition to my near-gaffe with menthe a l’eau, Romain said I need to include an apéritif called Zinzano in the book, which he said was très français.

Internet searches revealed nothing by that name, and it wasn’t until almost a year later, when I was touring the Byrrh distillery did I learn from my guide, who mentioned that they also make Suze and Zinzano in the adjacent facilities, that Zinzano was…Cinzano. Those were closed to the public, in spite of some insistent begging on my part.

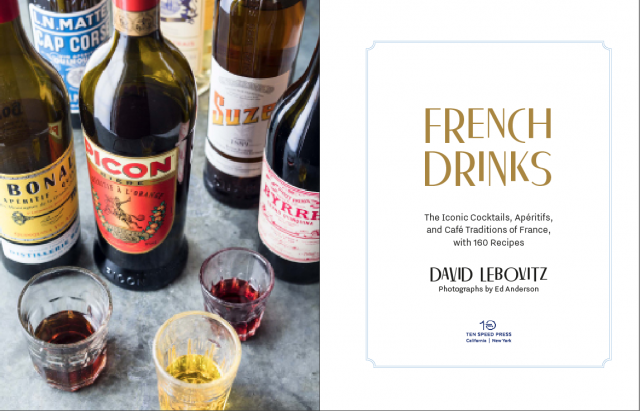

As I traveled, wrote, and mixed up apéritifs and cocktails, my apartment soon became loaded with French liquors and spirits of all kinds, and from all places, such as Dijon, Cognac, Corsica, Gascony, the Auvergne, Poissy, Provence, and Mexico. I know, you weren’t expecting that last one, were you? But yes, there’s even a French-Mexican liqueur I discovered in my travels.

That’s just part of my collection, which I may have to donate to a bar…or do I just need to have the most amazing French spirits and cocktails party ever?

But I didn’t buy everything. My DIY streak got the best of me and I included an entire chapter of homemade infusions, liqueurs, cordials, crèmes, and rum punches in Drinking French. A genial Michelin-starred chef in Paris led me to his private cabinets holding all sorts of homemade fruits and botanicals mysteriously bobbing in various liquids.

I came away with a recipe from him, as well as a tropically-tinged rum sourced from a chocolate shop owner in Paris, whose nanny from Martinique developed for the shop. I also came up with cocktails that used the homemade infusions, like a Chocolate Old-Fashioned with a shot of homemade Crème de cacao (page 156…don’t worry, it’s not sweet), and a Spruce tip martini (page 153.)

Once the recipes and writing were done, the finished manuscript was sent to my editor. In retrospect, I probably should have accompanied it with a few bottles. After turning in my manuscript, my next task was to reconnect with all my friends who disassociated with me because I was buried deep in my book, from 6am to 6pm, seven days a week, and abandoned me because I never had time to see them. When you write, sometimes the only people you connect with are other writers because they know what you are going through and when you say, “I can’t see you for the next eight months,” they’re not offended.

Manuscripts go through a few revisions. The first is a developmental edit, where any large-scale issues are addressed. Things like “Cut this section,” or “Can you expand on this?” might be noted by your editor, as well as anything they think should be moved around in the book. (My editor once put a note next to a story I wrote about being physically aroused by a dessert, with a note that said “Too much…” in the margin next to it. Which is why writers, especially this one, needs editors.)

After you check all of their recommendations and take those into consideration, you have a few weeks to revise as you see fit. Once again, you go back into hiding. Sometimes you agree and sometimes not. Writing a book is a collaboration between you and your editor. I’ve worked with mine before so we know each other and don’t have any issues. If I disagree on something, we discuss. Sometimes she’s right, other times, I want to keep things as they are. Btw: You can thank her for sparing you reading about my turgid tale.

When that round is over, the newly polished manuscript goes to a copy editor who scrupulously goes through everything, word-by-word, making sure you’ve included all the ingredients listed in the recipe in the instructions. That you’ve used the right words and got your metric conversions correct, if you use them, as I do. (Which often makes you feel like you’re writing two different books.) Hopefully they’ve caught any typos and grammatical gaffes. This copy edit is one of the most challenging for cookbook authors as there are lots and lots of details in each recipe, and it’s easy to miss one in the flurry of testing and writing up the recipe. You don’t want to see the “1/2 cup baking powder” I once saw in a biscotti recipe in a cookbook, that I’m sure the author meant to be either “1/2 teaspoon” or “1/2 tablespoon.”

I have a great recipe tester who takes good notes, which I keep and incorporate any tips or pointers that a reader might want to have. She’s not a professional cook (she now works in technology), but did go to cooking school. I sent her the recipes in the last chapter of the book, the Snacks chapter, without any guidance because I wanted to see how they came out as written in the book, not as I told her to make them. After making the recipes, she replied with notes and photos. Fortunately all of them came back with a big thumb’s up – whew!

While I was back-and-forthing with my editor, and the copy editor, the production editor, and the proofreader, the book was sent to someone for a “cold read,” which means they hadn’t seen the book so they were looking at it with fresh eyes, the designer began working on the layout and fonts, and it was time to take the photos.

Oh, yeah. Sorry. I probably should give a little more information about the last chapter in the book, which is devoted to things to eat that go with the drinks. I got my hands on the incredible Cheese and Seed Crisps (below, page 249) made by Market Hall Foods that once I tasted at a book signing I did there, I knew I had to put in the book.

There’s a super-simple terrine; if you can make meatloaf, you can make this French terrine. For those with a little more ambition, there are crisp, buttery Mushroom and Roquefort Tartlets (page 256) that go great with a glass of white or red wine. And while cornmeal isn’t exactly a French staple, my local natural food stores sell it, which I use for Cornmeal, Bacon and Sun-dried Tomato Madeleines (page 259). I also explain what Champagne truffles (page 269) are really made with (Spoiler: It isn’t champagne), and include a recipe for those, too.

Okay…where was I? Oh, yes, the photographs. I got to work with Ed Anderson again, who spent a few weeks in the kitchen with me, and walking around Paris, while he shot My Paris Kitchen. He also took the pictures for the updated edition of The Perfect Scoop.

I was happy to have him back for Drinking French. And I’m no food stylist, so I was thrilled that George Dolece was available and willing to take on the task of making sure everything was right in place. George lived in Paris, and I’ve known him from my San Francisco days, so we had fun playing around in front of – and occasionally when Ed would let us – behind the camera. To see what things looked like.

While we were doing that, the designer at Ten Speed, Betsy Stromberg kindly answered my fifteen thousand emails about fonts for the book. Fortunately, she geeked out on fonts as much as I did and showed me mock-ups using a number of them that she’d discovered. One thing I should insert in here right now is that it’s highly unusual to let an author have any contact with the book designer. The exchanges are always done through an editor, and the author rarely is allowed any serious input. Because I have a blog, I’m used to having total control over everything and can get rather type-A about even the littlest things. And it’s hard for me to give that up. But it’s nice to collaborate with people who are more talented and experienced than I am, which is why I love working with my publisher.

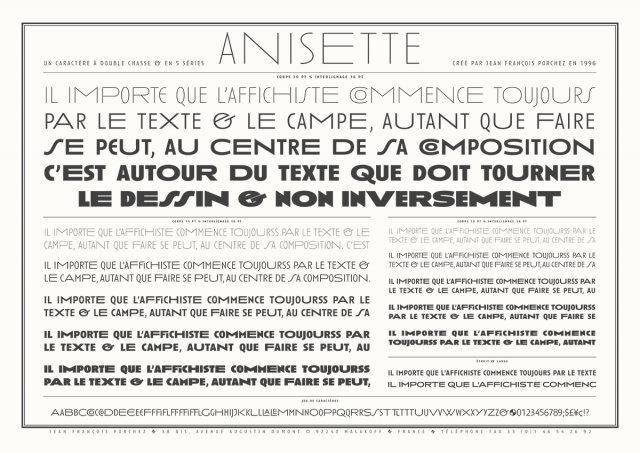

Because Drinking French spotlights French traditions and culture through stories, recipes, and photos, I felt the book needed a font that squarely looked French. It needed to be not only timeless but to look a little old and vaguely nostalgic, but without being heavy-handed, cliché, or overwrought. (I know. That’s a big order to fill.) People at Ten Speed liked the one above, but I didn’t think it looked very French. Betsy (kindly, and gently) reminded me that it’s called Le François, which was a pretty strong argument against my case, and for that font. Still, I didn’t love it. I did have to eat my words in the end, as once I had seen that font, I started seeing it around Paris in signage and on menus.

I loved the font above, called Anisette, which seemed appropriate for a couple of reasons. One was that anisette is a traditional French drink, similar to pastis, a widely consumed drink in France and gets mentioned several times in the book, along with a recipe for making your own. We went back and forth for a couple of weeks, while the production deadline loomed and the book needed to be sent to the printers in order to meet the March 3rd release date. This is just one of the many notes and emails I sent about the fonts while were looking at them:

Yes, that was just one of many, and yes, for the record…the people at Ten Speed are still speaking to me. But I was definitely cutting it close. One of my better qualities, however, is admitting when I’m wrong. And she was right about Assiette being a little hard to read, sending me a trial to look at, below. That font does look pretty loopy even though I really like it. Some things you think might work, don’t. So it’s worth taking a look at different versions than what you think you want and not being so fixed on your opinion of things. Another one of the many things I’ve learned about life.

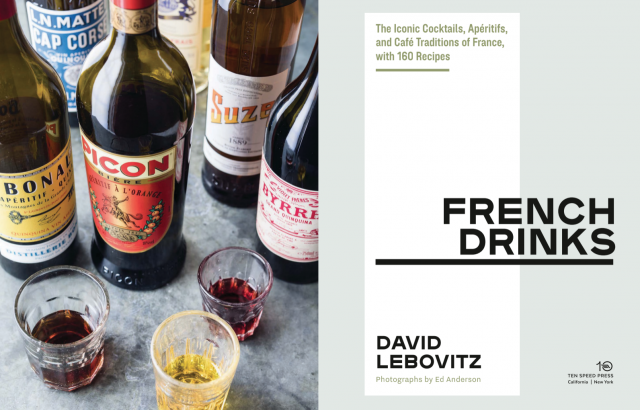

Finally, I was sent the mock-up below, using another font she found, which I agreed worked perfectly. Yay! I could feel the collective sigh of relief 6000 miles away from their office in California.

Another thing that got tweaked was the name of book. The working title was French Drinks but I was having lunch with Aaron Wehner, the publisher in New York, and before we parted, he said, “Oh…one more thing: What do you think about changing the name of the book?” I wasn’t married to French Drinks; it was just a placeholder that I had been using to refer to the book.

We just sort of rolled with it until he brought up another idea. He suggested Drinking French, which had more “action” to it, and I was fine with that. So it ultimately became this…

In the end, I couldn’t be happier with how the book came out; the photos, the fonts, the stories, and the recipes, all in one beautiful book. A few people at my publisher have PTDS, post-traumatic David syndrome. But I am sure a few rounds of cocktails (from Drinking French) will make us all amis again. And that’s how the book happened. I hope everyone enjoys it as much as I did putting it together!

Drinking French will be out March 3rd. You can pre-order a copy from your local bookseller, or online from a variety of independent booksellers, such as Book Larder, White Whale, Kitchen Arts and Letters, Omnivore, Powell’s, Now Serving, Strand, Archestratus, and RJ Julia. Drinking French is also available on Amazon, Indiebound, and Barnes & Noble, which is also offering autographed copies. (Quantities limited.)

Global readers can order Drinking French from Book Depository, which has free international shipping.

[The opening hot chocolate picture, the chocolate frappé photo, and the café breakfast photo shown, are from the book by Ed Anderson.]